Indiana World War Memorial Plaza

Origins and development of the 25 acre memorial plaza

Introduction

The Indiana World War Memorial Plaza was the largest and most elaborate tribute to the sacrifices of World War I veterans constructed anywhere in the United States. It symbolizes the role of patriotic values to an Indianapolis culture and remains one of the nation’s most significant memorial sites.

Indiana World War Memorial Plaza, ca. 2013 Credit: Indiana War Memorials Commission

Before the Monument

The Plaza Site in 1919

In 1919, the five-block long site for the future Indiana World War Memorial Plaza was occupied by a mixture of city parks, a state institution for the education of the blind, churches, apartment buildings, office buildings, private residences, a cultural institution, and several stores. The block at the south end, University Square, bounded by New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Meridian, had served as a city park since 1865.

Swipe to compare the plaza in 1916 and 2020.

The northern two blocks of the future plaza site ran without interruption between North and St. Clair Streets. The Indiana School for the Blind occupied the southern half, fronting on North Street, and St. Clair Park occupied the northern parcel. Both properties were owned by the State of Indiana.

At south end of the five-block-long site stood the U.S. Courthouse and Post Office, built between 1902 and 1905, and at the north end was the Indianapolis Public Library, constructed between 1915 and 1917. These two buildings with neoclassical designs would play key roles in the design of the plaza.

Building the Monument

American Legion Chooses Indianapolis

World War I, the “war to end all wars,” halted with an armistice on November 11, 1918. When soldiers and sailors met in Paris in the spring of 1919 to discuss forming the American Legion for war veterans, Indianapolis made a bid for its permanent national headquarters. At a November 2019 convention in Minneapolis, Indianapolis ultimately edged out Washington, D.C., Kansas City, and several other cities, thanks to intense lobbying and an emphasis on the city’s central location in the country and its easy access by rail.

(From Left) Col. Robert Moorhead, Dr. T. Victor Keene, Walter Myers Jr.–the three Hoosier Legionnaires who led the successful effort to locate the national headquarters of the American Legion in Indianapolis Credit: The Indiana Album: Joan Hostetler Collection ( Keene and Myers ); Find a Grave ( Moorhead )

Scene from the first American Legion Convention in Minneapolis, November 1919 Credit: Minnesota Historical Society View Source

The State Agrees to Build a Headquarters and a Memorial

State and city leaders proposed to build a combined Legion headquarters and war memorial to Indiana veterans of World War I similar to the Civil War-themed Indiana Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on the Circle. In July 1920, the General Assembly passed a law dedicating the northern two state-owned blocks of the plaza site to the location for a memorial and Legion headquarters, appropriated $2 million for the cost of developing and building, created an Indiana War Memorials Commission to oversee the project, and provided for approval by the commission of the design for any future buildings constructed within 300 feet of the plaza. The legislature’s swift move confirmed Indianapolis as the site of the Legion headquarters. In November 1921, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the commander-in-chief of the Allied forces in France in 1918, visited Indianapolis and dedicated the future site of the World War Memorial Plaza.

From Left: James P. Goodrich, Governor of Indiana 1917-1921; Charles W. Jewett, Mayor of Indianapolis, 1918—1922; Marshal Ferdinand Foch Credit: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons ( Goodrich ); Oversize Photograph Collection, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library ( Jewett ); Indiana State Library and Historical Bureau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons ( Foch )

The National Architectural Competition

The trustees of the War Memorials Commission held a national architectural competition for a compelling design for the War Memorial Plaza. Three nationally eminent architects served as jurors to recommend a winner from the 25 qualified entries received by April, 1923. In the blind selection process, the winning design was submitted by Frank R. Walker and Henry E. Weeks of Cleveland.

Frank R. Walker and Harry E. Weeks Credit: Indianapolis News

Profile: Walker and Weeks

The architects who won the competition—Frank R. Walker and Harry E. Weeks—headed an influential firm based in Cleveland. Both were graduates of the architectural program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Walker had undertaken advanced study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, one of the leading architectural schools in Europe. In Cleveland, the firm designed leading civic buildings, including the Cleveland Public Library, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, the Cleveland Post Office, the Municipal Stadium, the Municipal Auditorium, and Severance Music Hall. Both men were trained in the Beaux Arts method of design that governed much of architectural practices in the United States in the early 20th century.

The Winning Design

The winning design embodied the Beaux Arts method. Its centerpiece was to be a monumental Memorial building in the block between Vermont and Michigan, a concept inspired by the Tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassus in Asia Minor, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The neoclassical design, siting, and scale of the memorial linked the similarly designed U.S. Courthouse one block to the south with the Greek classical façade of the Indianapolis Central Library three blocks to the north. Another unifying element was the use of Indiana limestone for all the buildings.

The Walker and Weeks design for the plaza incorporated the Beaux Arts emphases on axes and dramatic terminating vistas. It also included a 100-foot-high obelisk, multiple fountains at center, a sunken grassy mall, and a cenotaph (monument) at various points.

Construction of First National Headquarters of the American Legion

Walker and Weeks designed the national headquarters building (“Building B”) as a four-story classical building that would pay deference to the Public Library to its north and the future Memorial Building to the south. The cornerstone was laid in 1924, and the building was completed in 1925 at a cost of $416,030, which was drawn from the initial $2 million appropriation made by the legislature in 1920.

During the 25 years that the national headquarters of the American Legion occupied Building B, the Legion became the largest veteran’s organization in American history, with a membership of 3.5 million by 1945.

Construction of the War Memorial Building

In 1926, the War Memorials Commission trustees moved to construct the Memorial Building itself (“Building A”), which required the removal of all buildings that stood on the block between Vermont and Michigan Streets. On the site was the First Baptist and Second Presbyterian Churches. The trustees could not reach agreement with the church congregations on purchasing their properties, so these churches remained on the plaza until 1960.

Excavation of the site began in 1926, and the foundation, basements, and ground floor structure were completed by the spring of 1927. On July 4, 1927, General John J. Pershing, commanding general of the American Expeditionary Force in World War I, laid the cornerstone after serving as grand marshal for a parade of 5,000 World War I veterans through downtown. Construction of the tower (pavilion) and pyramidal roof took shape in the rest of 1927 and was completed in the fall of 1928. Funds ran out for completing the Shrine Room, the auditorium, or meeting rooms in 1928, so only the exterior was finished at that time.

Construction of Obelisk Square

The War Memorial Commission next turned to creation of Obelisk Square, in the block immediately north of the War Memorial. The 100-foot obelisk, a memorial symbol going back in its origins to ancient Egyptian culture, was completed by 1930. Most of the surface of Obelisk Square was paved, leaving the space open for gatherings and for an unobstructed sight line along the main axis running through the center of the square between the Memorial Building and the public library.

Construction of Cenotaph, Sunken Garden and Mall

In 1930, the War Memorial Commission demolished the buildings of the Indiana School for the Blind on the block north of North Street and began the excavation and grading necessary to construct the mall, sunken garden, and cenotaph between Obelisk Square and the public library. The rectangular cenotaph was a symbolic tomb for all service members who lost their lives during World War I. On the north side of the cenotaph was placed a bronze plaque in memory of Corporal James Bethel Gresham of Evansville, Indiana, the first member of the American Expeditionary Force to lose his life in the war. The cenotaph was dedicated in 1932.

Corporal James B. Gresham, ca. 1914 Credit: Indiana State Library View Source

Profile: Corporal James Bethel Gresham

Corporal James Bethel Gresham (1893-1917) was born in Evansville and enlisted in the U.S. Army as a career soldier in 1914. In 1916 he served under General John J. Pershing during his expedition to Mexico and in the fall of 1917, Gresham was among the first American troops to be shipped over to France to join the Allies in World War I. On November 2, 1917, Corporal Gresham and infantry unit were serving in the French battle line extending through Lorraine, in northeastern France, when German shock troops attacked Gresham and his platoon. Despite being greatly outnumbered, Corporal Gresham and two of his comrades fought fiercely and lost their lives combatting the attack. Gresham was identified as the first member of the American Expeditionary Force to lose his life in action during the First World War. After the war, Gresham’s mother requested that his body be returned home and in November, 1921, his body lay in the Statehouse rotunda as the State of Indiana conducted public funeral. He was laid to final rest in Locust Hill Cemetery, Evansville.

Completion of Shrine Room

In 1931, the state funded the interior design of the lofty Shrine Room in the War Memorial and the auditorium, the vestibule, foyer, and meeting rooms on the ground floor. Dedicated in 1933, the space was of monumental scale, brilliant colors, costly materials, and a powerful interpretive program through sculptures, paintings, and symbolism. The whole was intended to inspire good citizenship by all who visit it.

Completion of Rest of War Memorial Building

A loan from the New Deal Public Works Administration in 1933 made possible the completion of the rooms on the ground floor and basement of the War Memorial. The central feature of the ground floor was the auditorium for patriotic events constructed directly below the Shrine Room. After World War II, the auditorium was named in honor of General John J. Pershing, and his portrait was placed on the rear wall of the speaking platform.

East and west of the foyer and the auditorium were constructed oak-paneled meeting rooms, each seating 200-250 people. Large rooms in the basement were finished for a future museum of artifacts recording the experience of World War I.

The finished interiors below the Shrine Room were dedicated in 1937. The total cost of construction for the entire plaza through 1937 was estimated at between $12 million and $15 million. For comparison, the Lincoln Memorial when completed in 1922 cost about $3 million.

Influence of War Memorial Plaza on the Design of Buildings Fronting the Plaza

Buildings constructed along the west side of Meridian Street and east side of Pennsylvania had to harmonize with the scale, materials, and style of the buildings, objects, and landscape design of the War Memorial Plaza. The final major building erected along the plaza during the 1920s was the monumental Scottish Rite Cathedral, costing $2 million. It drew inspiration from English cathedrals, in laying out a nave, a crossing tower, and a choir and scaled all but the tower to pay deference to the War Memorial. The single feature that was comparable in height to the Memorial—the tower--was a single vertical accent that did not compete directly with elements of the plaza.

Construction of New National Legion Headquarters Building

In 1944, in anticipation of a large increase in membership arising from returning World War II veterans, the American Legion requested that the State of Indiana construct three new buildings on the two sides of the Cenotaph, but the General Assembly appropriated funds only for the new national Legion headquarters.

Completion of Plaza with Removal of Churches

After World War II, the American Legion began to advocate for removal of the churches and completion of the World War Memorial Plaza design. Finally, in 1955, the Indiana General Assembly appropriated $800,000 for the purchases of the two church properties, and in 1957 the congregations agreed to sell their parcels. Demolition occurred in 1960, with the space used to complete the landscape design of the War Memorial on the two corners.

Another feature of the War Memorial that urgently needed action was establishment of the military museum intended for the basement of the War Memorial. The lower level had stood vacant since the 1930s. Artifacts from World War I, World War II, and other conflicts were gathered and installed beginning in 1962 and the museum was completed in 1965.

Sculptures of the War Memorial Plaza

Allegorical Sculptures

Henry Hering

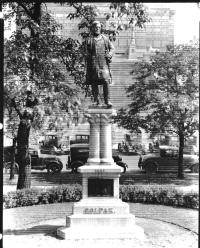

Schuyler Colfax Memorial

Lorado Taft

Depew Memorial Fountain

Karl Bitter and Stirling Calder

Benjamin Harrison Memorial

Charles Niehaus and Henry Bacon

Abraham Lincoln Memorial

Henry Haring

Pro Patria Statue

Henry Haring

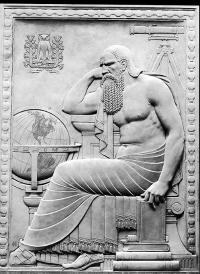

Relief on obelisk

Henry Haring

Additions and Renovations

New Designs for Obelisk Square

Obelisk Square, as designed in the 1920s, was to be a square with a striking centerpiece—the black granite obelisk, with its bas relief tablets, surrounded by an elaborate fountain. Most of the square as built, however, was covered with an asphalt surface. In 1975, a redesign of the site, as part of beautification efforts to mark the Bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence, added grassy areas, brick pavements, and trees at the four corners. Obelisk Square was renamed Veterans Memorial Plaza.

Obelisk Square as re-designed by Browning Day Pollack in 1975 and re-named Veterans Memorial Plaza. Credit: War Memorials Commission

In 2004, the Indiana War Memorials Commission replaced the 1975 alterations with a design that provided more continuity between the landscape design of the War Memorial block and that of the American Legion Mall blocks. The new design strengthened the principal north-south axis of the War Memorial Plaza with diagonal walks from the four corners of the square to the central Obelisk promenade, like those found in University Park. Two, parallel east-west walks provided pedestrian access to the Obelisk from Meridian and Pennsylvania.

Memorials for World War II, Korean War, and War in Vietnam Veterans

From the late 1920s to the early 1990s, the principal features of the World War Memorial Plaza served to commemorate the sacrifices only of Indiana World War I veterans. In 1993, the Indiana Department of Veterans Affairs and Indiana War Memorials Commission decided to incorporate into the plaza design memorials for three conflicts since World War I—World War II, the Korean War, and the War in Vietnam. The memorials for the Korean War and the War in Vietnam were constructed first and dedicated in 1996. The two memorials were designed to complement each other. Together, their partial cylinders make up a complete cylinder. The War in Vietnam Memorial is larger because of the greater number of veterans who lost their lives. All three memorials were designed by Patrick Bruner.

Designation as a National Historic Landmark District

As the largest and most elaborate memorial in the United States to the sacrifices of World War I veterans, the World War Memorial Plaza has considerable historical significance. In 1994, the War Memorials Commission, Indiana Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology, Indiana Landmarks, and National Park Service cooperated to secure its designation as National Historic Landmark District. In 2016, the Park Service amended the nomination for the Landmark District to include the nationally significant Indiana Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, and the district is now known as the Indiana War Memorials National Historic Landmark District.

Restoration of the Plaza

Over the past two decades has undertaken major restoration projects along the plaza and adopted a regular schedule for maintenance of the many historic features. In University Park, the commission and Department of Administration have restored the surfaces of the bronze statues of Vice President Schuyler Colfax and President Abraham Lincoln and rehabilitated the Depew Memorial Fountain. On the War Memorial building itself, the War Memorials Commission and Indiana Department of Administration has restored the statue Pro Patria and spent $2.9 million between 2018 and 2020 to replace the granite slabs that covered the steps of the pyramidal roof and some of the limestone veneer.

Community Uses

In recent years, the Indiana War Memorials Commission has made available the American Legion Mall and the Veterans Memorial Plaza for a variety of public events and private rentals. A popular community event is the annual 4th Fest in the Veterans Memorial Plaza, celebrating the Fourth of July. Another is the Indianapolis Public Schools’ annual “Back to School Festival.” In the War Memorial Building, the War Memorials Commission makes available the Pershing Auditorium for funerals of Indiana veterans. In the basement and main floor, the War Memorials Commission since 2005 has developed a comprehensive Indiana War Memorial Museum that interprets the roles of Indiana veterans in all wars since 1800 and displays artifacts with Indiana connections from all of those conflicts.