Southern Drinking Culture

Alcohol and Temperance as a Cultural Process Over Time

The Frontier South

The consumption of alcohol is an integral part of Southern culture, dating back to its earliest days as an untamed frontier. Even with the little resources they had, the settlers made many different kinds of drink, depending on what crops were in season at the time. For example, in the fall, beer made from persimmons was popular. Pioneers also drank hard cider and rum. They made brandy from peaches, primarily in Georgia. However, the most famous and popular frontier alcohol was corn whiskey. It was one of the biggest cultural contributions made by the many Scots-Irish immigrants who came to the South. Frontiersmen consumed whiskey in enormous quantities. With sparse neighbors and little things to do once the day’s work was done, most frontier farmers would relax under a tree with a jug of corn whiskey. Even babies and mothers drank weak toddies for perceived health benefits. Although they consumed quite a bit of alcohol, people on the frontier were likely not drunk constantly. They had a fear of Native American attacks that caused them to stay somewhat vigilant.

The Antebellum Years

As settlers populated the frontier and established farms tilled by African slaves, three primary classes emerged from the plantation system - the poor whites, the rich planters, and the slaves. As the socio-economic structure of the South evolved from Frontier into the Old South, so too did the culture of alcohol consumption.

Poor whites didn’t produce much beer or ale. Native-grown wines were considered bad. Foreign wines were much too expensive for the common white. They did enjoy peach brandy, but the most popular spirit by far was still corn whiskey. The first recorded mention of the mint julep, a cocktail containing mint, sugar, and whiskey, was in 1814. However, most Southerners, especially men, took their whiskey straight. A whiskey barrel was a requirement for good hospitality or any proper celebration. The lonely pioneer drinking corn whiskey under a tree had evolved into a whole group partaking in the spirit together.

The biggest difference between the poor and rich whites was that the rich had the pleasure of drinking imported wines. Straight liquor was less common and usually mixed, likely in a toddy or some eggnog. The most culturally iconic cocktail that emerged out of antebellum planter drinking culture was the mint julep. The image of the Old South aristocrat drinking a mint julep on the porch just after waking up in the morning is now iconic. This cocktail, which is served chilled, likely owed some of its popularity to the brutally hot weather in the South. While visiting a plantation near New Orleans, William Howard Russell called the mint julep “a panacea for all the evils of climate.” Although it was illegal to sell liquor to slaves, they often acquired it anyway. There was always someone who wanted to make a buck, and slaves could discreetely buy or trade for some whiskey. This provoked great anger in slave owners, as a drunk or hungover slave was not a productive one.

The antebellum years brought the beginning of the temperance movement in the South. Early temperance advocates were evangelicals, primarily Baptists and Methodists. but they did not garner much support during this period. They had the least supporters anywhere in the country and provoked hostility from drinkers. In the North, the temperance movement had a close association with abolitionism. Most organizations that campaigned for temperance had public ties with abolitionists. This damaged their image in the eyes of slave owners and other slavery supporters. They were often harassed or pushed out of cities for their views. However, this did not totally crush the movement. To increase their appeal, Southern temperance advocates separated themselves from Northern organizations that included abolitionists. Most of these supporters were middle class artisans from cities and towns. Poor whites and the elite planters were not interested in having their beloved corn whiskey taken away. Many rich planters initially supported temperance to get liquor taken away from slaves. When it became clear that their right to drink would come with that, they abandoned their support. Not only was social drinking an important piece in the lives of Southern gentry, ‘conspicuous consumption’ worked as a display of their attitudes to the North. Economic constraints kept temperance from picking up in rural areas. Corn liquor was easier to transport, sell, and market than raw corn. It was sold for cheap at a quarter a gallon, which was less than a quarter of an artisan’s daily wage. This liquor was so widespread that it was substituted for money in more remote areas. One of the biggest reasons that temperance didn’t pick up in the antebellum years was that alcohol was deeply ingrained in the Southern work culture. Southerners had a tendency to mix work and leisure. Drinking on the job was not uncommon. The South lacked the North’s tight work schedules. In the United States, temperance grew in rural areas that were becoming more urban, which would not happen in the South until after the Civil War.

The New South

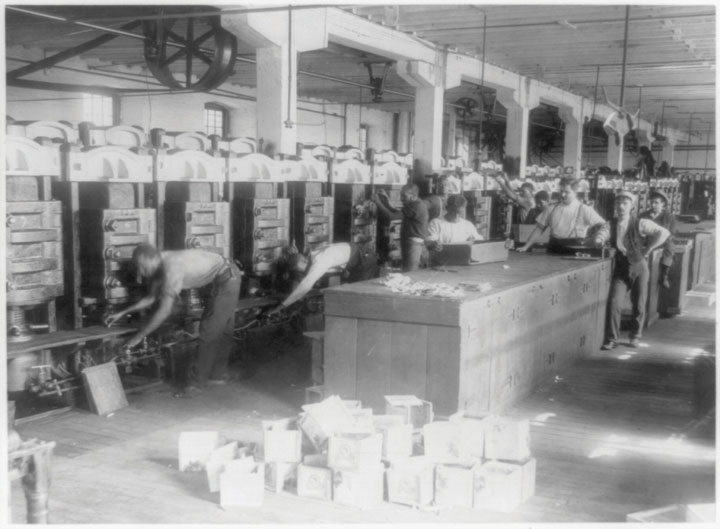

After the Civil War, large parts of the South transitioned from rural to urban communities. Entire cities, such as Birmingham, were founded or restructured to take advantage of factories and industrialization. The factories brought in lots of workers, both white and black, and the workers wanted their alcohol. Even as the South changed, drinking retained its traditional role in socialization and relaxation. Restaurants that served alcohol were very popular. In Montgomery, the connection between eating and drinking was so tight that restaurant owners assumed their business license also meant they could sell alcohol. The chief of police complained that allowing restaurants to be open on Sunday meant alcohol was being sold on Sunday.

Evangelicalism continued to spread, and with it came temperance. Evangelicals had a pessimistic view of human nature, and believed that the presence of immorality anywhere would tempt well-meaning Christians. They argued that peer pressure and proximity to public drinkers would cause more people to indulge in spirits. The most dangerous kind of drinking was the social drink, which was assumed to lead to sexual immorality and debauchery. In the New South era, temperance supporters had the influence to impose social and legal control over alcohol. Michael Lewis, in his article Keeping Sin from Sacred Spaces, asserts that the control over morality to protect others from falling into degeneracy was a staple of Southern Christian culture. The divide between Southern drinkers and temperance advocates illustrates this phenomenon. Evangelicals took up the task of destroying the city saloon so that non-drinkers wouldn’t be tempted. There were attempts, many unsuccessful, to separate eating and drinking by restricting the sale of alcohol in restaurants. They instituted Disturbing Public Worship laws, or DPWs, which made it illegal to drink, possess alcohol, or be intoxicated on church grounds. Looking at records of police being called to churches, it appears Southerners were very willing to cite these laws to any offenders. As Lewis puts it, “Only in the South were activities involving alcohol in and around sacred spaces specifically condemned by law.”

By 1887, every state in the South had some form of no-license laws, creating specific areas where saloons and liquor stores could not exist, such as near schools or playgrounds. Many Southern counties did away with saloons entirely by adopting the dispensary system. A dispensary was a cold, lifeless government building where drinking was prohibited, by those who desired it had to get their alcohol there. With dispensaries, the purchase of alcohol was much less alluring. Even with all these measures taken, temperance advocates still could not stand having their dry counties next to a wet one, as they believed the nearby presence of drinking continued to infect their spaces. As the economic and social structure of the South changed, drinking culture adapted to the New South way of life, and new opponents rose up to suppress it.

Prohibition Decline

At the turn of the twentieth century, anti-drinking sentiment reached an all-time high. Even before the 18th Amendment was ratified, outlawing all alcoholic beverages in America, all southern states save Louisiana embraced statewide prohibition. However, prohibition had the opposite of its intended effects. Instead of ridding the South of alcohol, bootleggers got wildly rich. These bootleggers made lower quality whiskey than traditional distillers, which they called moonshine. Most Southern drinkers considered the taste revolting, but the alcohol content was so high that it was excellent for partying and forgetting a man’s woes. Prohibition forced drinking to become a private activity, changing the Southern culture of consumption. The near-universal use of spirits once enjoyed by antebellum men finally came to an end. After the end of Prohibition, the stigma surrounding alcohol planted by evangelicals remained in Southern culture, and it has never recovered its widespread public utilization. Lewis effectively summarizes the long-term effects of the evolution of Southern drinking culture: “All southern states also continued the practice of allowing local prohibition as an option, giving rise to a regionally unique patchwork of dry counties across the South that continues to this day. Finally, southern states continued to protect churches and schools through laws that limit where liquor can be sold.”

Sources

Berry, Chad. “The Great ‘White’ Migration, Alcohol, and the Transplantation of Southern Protestant Churches.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 94, no. 3 (1996): 265–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23383859 .

Carlson, Douglas W. “‘Drinks He to His Own Undoing’: Temperance Ideology in the Deep South.” Journal of the Early Republic 18, no. 4 (1998): 659–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/3124783 .

Cooley, Angela Jill. To Live and Dine in Dixie: The Evolution of Urban Food Culture in the Jim Crow South. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 2015.

Harris, Trudier. “Porch-Sitting as a Creative Southern Tradition.” Southern Cultures 2, no. 3/4 (1996): 441–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26235483.

Lewis, Michael. “Keeping Sin from Sacred Spaces: Southern Evangelicals and the Socio-Legal Control of Alcohol, 1865–1915.” Southern Cultures 15, no. 2 (2009): 40–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26214207 .

Stewart, Bruce E. “Select Men of Sober and Industrious Habits: Alcohol Reform and Social Conflict in Antebellum Appalachia.” The Journal of Southern History 73, no. 2 (2007): 289–322. https://doi.org/10.2307/27649399.

Taylor, Joe Gray. Eating, Drinking, and Visiting in the South: An Informal History. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2008.

Tyrrell, Ian R. “Drink and Temperance in the Antebellum South: An Overview and Interpretation.” The Journal of Southern History 48, no. 4 (1982): 485–510. https://doi.org/10.2307/2207850.

Wagner, Michael A. “‘As Gold Is Tried In The Fire, So Hearts Must Be Tried By Pain’: The Temperance Movement in Georgia and the Local Option Law of 1885.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 93, no. 1 (2009): 30–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40585114.

Images

https://miro.medium.com/max/1068/0*tc6gWYq1yRYWgN_z.

https://images.fineartamerica.com/images/artworkimages/mediumlarge/1/kentucky-landscape-james-pierce-barton.jpg

https://mizzouweekly.missouri.edu/archive/2013/34-25/corps/lead.jpg

https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_a-history-of-the-united-states-vol-2/section_05/b1b7f0253e1a64cf24c5443642fb8237.jpg

https://sharetngov.tnsosfiles.com/tsla/exhibits/prohibition/images/moonshine/6847.jpg