Why GIS Matters in Maine

From the economy to natural resources, from tourism to climate adaptation, Maine has never needed geospatial technologies more.

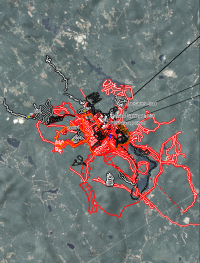

Fairmount Cemetery Web Map

Funded by two Maine Economic Improvement Fund (MEIF) grants awarded to a research team led by Drs. Chunzeng Wang, Mike Sonntag, Lynn Eldershaw, and Kimberly Sebold, the University of Maine at Presque Isle (UMPI) has conducted burial data collection and GIS mapping and data integration of the Fairmount Cemetery since summer 2009. Thirteen UMPI students assisted the project by performing cemetery data collection and database development, as well as data online publication. Professor JoAnne Wallingford supervised Access database management system development and initial website design. The project is the first large-scale, comprehensive cemetery mapping with applications of advanced GPS, GIS, and web GIS technologies in Maine. The database serves as a cultural resource for conservation, interment planning, maintenance of grave markers and monuments, and management of facilities, grounds, and records. The project is expected to have direct economic impact on the region in terms of availability to and attraction of tourism, while it provides the public with a solid database for genealogical and historic research. The project has fostered a fruitful connection between faculty, students, and community associations, most notably, the Fairmont Cemetery Association and the Presque Isle Historical Society. Participation of students in the project has gained them hands-on experience that has enhanced their academic experience and employable skills. The alliance between students, faculty, and community serves as a good example of service-learning and community-based research. Link to Fairmount Cemetery project page Link to web map Project information and image credit: University of Maine at Presque Isle GIS Laboratory

Online Parcel Maps

The digital parcel maps for Easton and Caribou, Maine are based on hard-copy tax maps that were updated in the Fall of 2014. The digital parcel maps were created in the GIS laboratory at the University of Maine at Presque Isle. The information gathered is made available thanks to the Maine Office of GIS and the Maine Geo Library. Link to Easton parcel web map Link to Caribou parcel web map Project information credit: University of Maine at Presque Isle GIS Laboratory Image credit: Town of Easton, Maine

Food Pantry Awareness and Accessibility

A story map created by Shanna Hobbs that details the distribution of food pantries across the state of Maine. Shanna's story map also includes data on population and income distribution across the state as well. This combination of data enables an in depth look at the overall access of food pantries in the state and whether the areas and communities that have the greatest need of them, have access to them. Click here to view a lightning talk by Shanna on her story map Project information and image credit: Shanna Hobbs with the University of Maine

Rails to Trails

Izaak Onos, a graduate student in the University of Southern Maine's Muskie School of Public Service, created a proposal to turn unused rail corridors in Maine into biking and pedestrian trails. With his map heavy proposal that he wrote for one of his GIS classes, he was able to generate a public push that turned into a bill to examine four unused rail corridors in Maine for future privately funded development as bicycle and pedestrian paths. They included a line from Westbrook to Fryeburg, another from Augusta to Brunswick and one more from Ellsworth to Calais. Of course, they started with the Portland-to-Yarmouth section that Onos had originally examined. Click here for more information on the Rails to Trails project Project information and image credit: The University of Southern Maine

Assisting Search and Rescue Teams

Before the adoption and common use of GPS technology areas to be searched were sketched out on a map, if a map of the area was available with enough detail, to sketch the boundaries of the search block. Actually searching the specified area was done with map, compass, flagging tape, and pace count alone. When possible physical features such as roads, trails, streams, power lines, rail road tracks etc. were used as boundaries. Unfortunately these features were not always located in convenient places to define a reasonable size search block. Most of the time now, we hand over our hand held GPS unit for the Maine Warden Service (MWS) for them to connect to their computer with various mapping software and they will load a search block into the unit. Many of today’s units are able to transfer data to other GPS units wirelessly, so once one team member has the block it can quickly and easily be shared across the team. The SAR team would then locate their assigned area and would “grid” the box. Usually there would be a GPS on each end of the grid search team saving their track. If any evidence is found a waypoint can be created and if necessary the coordinates can be radioed to the MWS. Once the area was searched the GPS would then be handed back to the MWS for them to save the tracks into a master SAR map with all of the others areas being searched. Some newer models also have satellite communication which would allow the MWS to monitor a search team in real time from the command post and send text messages via satellite overcoming the shortfalls of radio or cell phone coverage. By having all of the team’s tracks the MWS can then determine if areas were covered well and if there are any holes in the search areas that need to be filled in. I remember seeing the map used for the Gerry Largay search. It looked like someone had taken a map and drawn small odd shaped boxes all over it and then someone had taken various colored markers and colored in all of the boxes. This image illustrates the full extent of the search pattern for an autistic man who was missing for more than a week near Lake Arrowhwead before his body was found. Project information credit: Bryan Courtois, with Pine Tree Search and Rescue Image credit: Josh Bubier Search Coordinator, with Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife

Finding Illegal Dumping Sites Using Aerial and Satellite Imagery

The University of Maine’s Wheatland Geospatial Lab has partnered with the New England Forestry Foundation (NEFF) to develop and apply working conservation easement monitoring methods for the Pingree and Downeast Lakes Forests Partnership conservation easements in Maine. Manual scans of recent satellite and aerial images are conducted by the Wheatland Lab, in order to find notable changes across the landscape. Through this, target sites that may pose threats to the easements are identified, which are often characterized by illegal dumping by third parties and occasional boundary encroachments. After being identified, more rigorous data analysis is done to confirm target sites, that will then be visited in person for ground truthing. This image illustrates an illegal dumping site in Washington County that was found by the team at the Wheatland Lab. Project information and image credit: Dave Sandilands, with the Wheatland Lab

Finding Rare Minerals Using LIDAR

A new deposit of rare minerals, often used in the construction of electronics, was recently found on Pennington Mountain. The deposit was found through a LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) mapping project of Northern Maine, being run by the Maine Geological Survey and the U.S. Geological Survey. The discovery of potentially mineable deposits of these minerals is fuel for additional surveying in the state to discover more. This mineral deposit is supposedly the first of its kind discovered East of the Mississippi River, which is an exciting prospect for the state of Maine. Project information credit: Nicole Ogrysko, with Maine Public Image credit: Chunzeng Wang, with the University of Maine at Presque Isle

Renewable Energy Siting Tool

The purpose of Maine Audubon’s Renewable Energy Siting Tool is to provide resources developers and decision-makers need to locate solar and land-based wind projects in areas that avoid or minimize negative impacts to important wildlife habitats. While many of the data layers are individually available elsewhere, the tool brings these datasets together into one map, and allows the visual display of the siting principles developed by Maine Audubon’s biologists and ecologists. Link to the Maine Audubon's story map with more information on the tool Link to the Renewable Energy Siting Tool Project information and image credit: Maine Audubon

Maine Healthy Beaches Dashboard

The Maine Healthy Beaches Program was established to ensure that Maine's saltwater beaches remain safe and clean. The program brings together communities to perform standardized monitoring of beach water quality, notifying the public of potential health risks and educating residents and visitors on what they can do to help keep Maine's beaches healthy. How do I know if it's safe to swim at my local beach? Check the Dashboard to see current beach status and advisories. Click here to visit the Maine Healthy Beaches website Project information and image credit: Maine Department of Environmental Protection

Community Intertidal Data Portal

The Community Intertidal Data Portal is a resource that was created to make intertidal data and information more accessible, foster connections between communities with an interest in the intertidal, and promote a more nuanced understanding of issues within the nearshore environment of Casco Bay. Some of the data products that the portal is linked to include a local shellfish conservation and management web application, a sea level rise infrastructure web application, and a balancing intertidal uses web application. Project information and image credit: Casco Bay Regional Shellfish Working Group

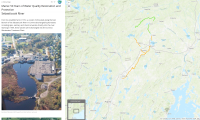

Maine: 50 Years of Water Quality Restoration and Protection

The Maine: 50 Years of Water Quality Restoration and Protection story map was created to cover the history of Maine's water quality protection program. The story map includes maps showing the history of Maine’s waters, as well as highlighting some case studies of rivers affected by various pollutants and how Maine and Federal water quality protection measures have helped to improve them over time. Click here to visit the story map Project information and image credit: Maine Department of Environmental Protection

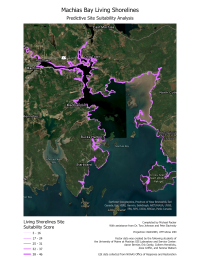

Living Shorelines Construction Suitability

With sea levels rising and stronger and more frequent storms, Maine coastal communities must decide the best way to prevent erosion and safeguard seaside structures. Hard structures such as rip-rap or sea walls can prevent erosion, but they can damage habitat and shift erosion to adjacent areas. Living shoreline solutions offer an alternative to hard structures with vegetation and porous material used to absorb wave energy and prevent erosion. Not every coastal location is suitable for living shoreline solutions. So, the University of Maine at Machias GIS Service Center used a method devised by Peter Solvinsky of the Maine Geological Survey to determine suitability for living shoreline for the shores of Machias Bay in Downeast Maine. Remotely sensed data is crucial to creating a living shoreline suitability model. The model utilized color infrared aerial and satellite imagery to identify vegetation and LidDAR (light detection and ranging) data, allowing 3D modeling of the nearshore environment. The map image shows the output of the model with thicker lines indicating higher suitability for living shoreline solutions. This map allows municipal officials and land conservation staff to make a preliminary determination about areas where living shoreline solutions may be viable. Project information credit: Dr. Tora Johnson, with the University of Maine at Machias' GIS Laboratory and Service Center Image credit: Mike Packer, with the University of Maine at Machias' GIS Laboratory and Service Center

Coastal Flood Planning Support

Rural communities need to make decisions about a wide array of environmental challenges with limited capacity to understand and assess such challenges. The University of Maine at Machias GIS Service Center provides mapping and decision support tools for municipal officials in the Downeast Region to aid them in these tasks. Students, faculty and staff create interactive maps, geospatial models, and other tools for municipal officials to use in important decisions related to land use planning, coastal resilience, and infrastructure. Remote sensing provides critical data sets for this work. This 3D visualization was constructed by combining color infrared imagery and LiDAR (light detection and ranging) and then virtually flooding the downtown areas of Lubec, Maine. This allows the community to see which lands, roadways, and water infrastructure is endangered by storm surges and rising sea levels. Project information credit: Dr. Tora Johnson, with the University of Maine at Machias' GIS Laboratory and Service Center Image credit: Trevor Riggin, with the University of Maine at Machias' GIS Laboratory and Service Center