Understanding Frederick Douglass

What do The Douglass Family Scrapbooks Show Us?

Our Mission

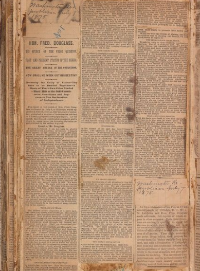

Did you know that scrapbooks were being made in the 19th Century? It is true, and one of the most significant ones of this time period is the Douglass Family Scrapbooks. If you want to learn more about these scrapbooks, as well as Frederick Douglass and the period of Reconstruction and the Civil War, check out this website! Looking through the lens of Douglass’ Composite Nation Speech, given in 1869 in Boston, we observed a few pages from the scrapbook and annotated them, specifically focusing on the themes of absolute equality, composite nationality, religious freedom and/or hope. We hope that by reading these pages and their notes, readers can get a better understanding of who Douglass was, as a leader and a family man, as well as what his beliefs were. Enjoy!

What are the Douglass Family Scrapbooks? Why are they important?

As many enslaved people were, Douglass was denied the knowledge of his birthday and who his father was, as well as the ability to see his mother and siblings. As a result Douglass never knew much about his own heritage, which left Douglass longing for familial connections his entire life. Slavery also robbed enslaved people of the opportunity to write their own narrative and make their own story, especially since enslavers believed that allowing enslaved people to read and write was a threat to the system of slavery. Despite this oppression, one of Douglass’s life goals was to create a long-lasting legacy that would give himself, his family and many other freedmen what he never had. Helping their father in this effort, Douglass’s children compiled eight scrapbooks, “The Douglass Family Scrapbooks,” documenting his and his family’s life, legacy and narrative using images, news articles and other sources from that time.

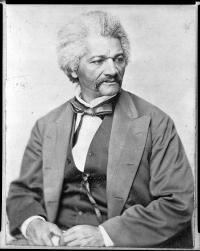

Who was Frederick Douglass?

Douglass's life

Douglass's life. Click to expand.

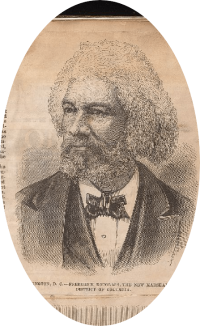

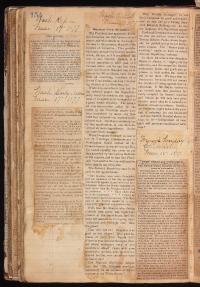

This following information about Douglass was recorded on page 211 in the first scrapbook. Douglass’ sons penciled in “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper NY April 7, 1877” to note where they had retrieved the clippings.

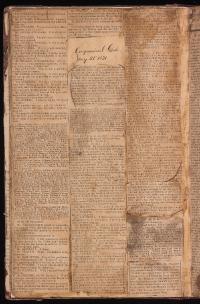

Pages 22-23: Congress during Reconstruction

Douglass Jr. and the Fight Against Racial Discrimination

Douglass Jr. and the Fight Against Racial Discrimination. Click to expand.

In May of 1869, Frederick Douglass Jr., Douglass’s second son, wrote a letter to DC’s Register of Deeds, Simon Wolf, asking for his application for clerkship to be considered. Douglass, an African-American who had faced discrimination and oppression, knew that there was racism in Government hiring. In the letter, he writes “I belong to that despised class which has not been known in the field of applicants for position under the Government heretofore.” Wolf, the recipient of the letter, was a Jewish immigrant from the German state of Bavaria. Throughout his life, he too faced hatred and prejudice. As a lawyer and personal friend of presidents from Lincoln to Harding, he fought for the rights of Jewish Americans. In his obituary in a Jewish newspaper, he was even referred to as “The Ambassador of the Jews at Washington.” In his response, Wolf writes that as a descendant of a similarly “maligned” race he has “a feeling of common cause” with Douglass. He finishes his letter stating that one day their two races will “become the head stone of our political and social structure.” Both Douglass Jr and Wolf have hope that, during Reconstruction, the racial and religious barrier can come down. This application is one step of many in the endeavor for absolute equality and religious liberty.

An Interesting Inclusion.

An Interesting Inclusion.. Click to expand.

It is unclear why this small article was included in the scrapbooks, but I will present two theories.

Congressional Debate on the Test Oath

Congressional Debate on the Test Oath. Click to expand.

During this session of the Forty-First Congress, the House of Representatives debated a bill (S. 218) that would abolish the Test Oath. Since 1862, when the Test Oath was enacted, all federal employees, including elected officials, had to swear that they had never been disloyal to the country to assume their post. By 1871, many people felt as though the Test Oath, also referred to as the Ironclad Oath, was an archaic law that unnecessarily restricted many people who had participated in the Confederate movement from being elected.

Butler’s Past

Butler’s Past. Click to expand.

During the Civil War, Benjamin F. Butler was one of the first Union generals to refuse to return fugitives from slavery to the Confederacy. When three enslaved people self-emancipated and escaped to Fort Monroe in Virginia, the fort he was in command of, Butler claimed that because the Southern States had seceded, the Fugitive Slave Act no longer applied. On top of that, he claimed that returning those who self-emancipated would mean directly supporting the Confederate war effort. His refusal was an important first step in protecting the freedom of the self-emancipated, and directly led to Congress passing the Confiscation Acts, laws that freed all “confiscated” enslaved people. Although it is clear that Butler cared about the rights of African Americans, it is important to note that the thousands of people who were freed by Butler and the Confiscation Acts faced severe oppression while living in military camps.

Congressman Butler’s Speech

Congressman Butler’s Speech. Click to expand.

In this transcript of the Congressional debate, Congressman Butler, the Chairman of the Reconstruction Committee, argues against the bill to repeal the Test Oath. He begins by saying that the Test Oath was established in a time of need, toward the beginning of the Civil War, and was a “measure of protection for the country.” Now, because of the rampant violence and “outrage” across the South against African-Americans and white Unionists, repealing the Test Oath would seem like appeasing a rebel force that had not given up the cause. “Whenever the men of the South will stop violence, stop outrage, and stop murder,” he says, “I will vote to remove political disabilities of every description.”

The Privilege of the Test Oath

The Privilege of the Test Oath. Click to expand.

Additionally, Butler viewed the Test Oath as a point of pride for the Union men living in both the North and the South. In his eyes, being able to say that they had never engaged in disloyal conduct was a privilege. He had been a General in the Union Army during the Civil War, and viewed his service with immense pride. In his own words, the Test Oath is a “sweet morsel under [his] tongue.”

Dangers of S. 218

Dangers of S. 218. Click to expand.

Butler then notes that if S. 218 is passed, any person, no matter the atrocities they’ve committed, would be eligible to be elected to the Senate or the House. He mentions Nathan Bedford Forrest, the KKK’s first Grand Wizard and a man who massacred both Black and white Union soldiers at the Battle of Fort Pillow, as a way to drive home this point. Forrest was one of the most hated men in the Union thanks to the widely publicized war crimes he committed during the war. By mentioning his eligibility, Butler hopes to show the potential danger of passing S. 218.

Pg 23: The results

Pg 23: The results . Click to expand.

After a brief argument between Butler and Democratic Congressman Thomas Jones (I suggest you read this; it lends some light on the pettiness of politicians) the vote is called, and the bill passes. So why did Douglass’ sons include this transcript in their archive? I believe that Butler’s speech shows the sentiment of many Republicans, both politicians and voters. The conflict between appeasement and reunification was one that was frequently argued throughout Reconstruction. Many Republicans felt that the actions of Congress were granting too many concessions to the Southern states as violence and riots resulted in the deaths of hundreds of African-Americans. While I could not find a record of Douglass speaking on this bill specifically, it is one example of many battles, including those that engaged Douglass, that were fought throughout the Reconstruction period.

Page 135: Letter to the Wash. Chronicle

Who is Gerrit Smith?

Who is Gerrit Smith? . Click to expand.

Gerrit was largely against slavery, essentially in-sync with the idea Douglass had of the enslaved being left alone. He believed that Black people deserved to be able to live freely, without living under the fear of others harassing them. Gerrit and Douglass even collaborated on a convention held in 1850 to protect the passage of the Fugitive Slave Bill. His sons likely included this because of the importance Gerrit held to Douglass, seeing as both of them were respected abolitionists.

Letter to the Wash. Chronicle: Purpose

Letter to the Wash. Chronicle: Purpose. Click to expand.

Douglass was unhappy with a letter published in the Washington Chronicle, signed by "A Colored Man." In response, Douglass writes his own letter, refuting the claims made by a "Colored Man." His response is entitled entitled "He Excoriates a 'Colored Man.'"

To The Editor of the Washington Chronicle

To The Editor of the Washington Chronicle. Click to expand.

Black people must speak out, despite the backlash they are receiving for expressing their opinions. Sitting and lying in silence is not something Douglass takes lightly, due to his strong beliefs of advocacy. Just like Douglass, it is up to all of us as a society to allow for a space where all voices can be heard, without being immediately silenced.

As Being Their Own fault

As Being Their Own fault. Click to expand.

Douglass considers it an insult when Black people say that their problems are “their fault,” because it sends a message to the enslavers that they deserve everything that they have gone through as an enslaved person. The struggle that they endured is one that Douglass believes will be credited to them in history textbooks if they continue to refer to their problems as their own fault. While they have undergone many hardships, they have had some success. Emancipation, to a limited extent, could be seen as one of those wins. However, it came about through much war and bloodshed as opposed to genuine remorse for slavery.

Freemen in the Evening

Freemen in the Evening. Click to expand.

There was a very sudden shift in roles; suddenly, enslaved people were free. But when they were freed, they were free with nothing. Their previous enslavers, in spite of the recently passed Emancipation, would either try to keep them under their control, but if they managed to escape, they would have no resources or help from the enslavers. All the land that they had tilled still belonged to the enslavers, as well as the crops that came with it. This led to a much different life for the previously enslaved. They no longer had to answer to their enslavers, but they would still have to undergo attempts from others to capture them, as well as general harassment.

Lamented Charles Sumner

Lamented Charles Sumner. Click to expand.

Charles Sumner, a well known advocate for the abolition of slavery before and after the Civil War, made a demand for the enfranchisement of Black people, whereas Senator Doolittle was in opposition due to his beliefs that they would have an “utter extinction, potentially due to the fact that Doolittle was a strong supporter of Lincoln, and he left the Democratic party. Black people however, have proven this statement wrong in the eyes of Douglass. In fact, Douglass believes that if it was not for the endurance that they held in the face of prejudice, Doolittle’s opposition may have been the end result. Their endurance is something that makes Douglass see as a sign to the enslavers on how Black people have, and will continue to be the “main wealth-producing agent in the south.”

But What Kind of A Blow

But What Kind of A Blow. Click to expand.

Douglass believes that Black people shouldn’t start an uprising against white people. He writes, "I am still for patience, for appeals to the sense of right in men, to Congress, to the President, to Faneuil Hall and Cooper Institute, and to every other source of moral and intellectual power."

Page 143: Speech at Hillsdale

Page 143: Speech at Hillsdale

Page 143: Speech at Hillsdale. Click to expand.

Some Historical Context

How Were Douglass’ Speeches Received and Shared?

How Were Douglass’ Speeches Received and Shared?. Click to expand.

The author of this article uses this section to address their belief that Douglass’ speech was misreported in the National Republican. Therefore, the speech has been transcribed “correctly” here. This paragraph compels the reader to consider how Douglass’ speeches were received and shared by others. In his time, Douglass was a popular, influential speaker, who inspired many people. John Stauffer, a curator, shared, “He was the preeminent writer and widely known in his day as the greatest orator in the 19th century…He was dedicated to giving speeches that would keep audiences on their seats, wanting to follow every word.” Because so many people attended his speeches, it can be inferred that they were altered based on bias. Nevertheless, many people still received Douglass’ speeches, even if they were not present, because of articles like this and even word of mouth. It is interesting, to also consider, that Douglass’ sons included this article and not the National Republican article which implies that this article is more accurate over the other.

Absolute Equality With One Word?

Absolute Equality With One Word?. Click to expand.

Douglass used his words intentionally. In this paragraph, he uses a general term, “men”, to describe the people affected in the American Revolution. Why is this important? Why doesn’t he make a distinction between Black men and White men? Douglass used this term often, to unite everyone under one humanity, regardless of their race. This was an important part of the fight for absolute equality for him, and other formerly enslaved people, who were often dehumanized and not seen as true men.

The Importance of the Fourth of July to African Americans!

The Importance of the Fourth of July to African Americans!. Click to expand.

In this paragraph, Douglass explains why the Fourth of July, as well as the numerous fights for America, are just as important to white men as they are to African American men. Douglass explains that African Americans were always fighting alongside their fellow Americans in these battles. Not only does this contribute to ideas of absolute equality because it touches on the joined fight, but also composite nationality. Historically, white people did not consider African Americans to be American because enslaved people were not even considered human. However, Douglass and the newly freedmen believed differently. As a matter of fact, they found great pride in fighting for their nation. Especially in the Civil War, Douglass urged President Lincoln to allow colored troops to fight because of their eagerness. He wrote, “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny he has earned the right to citizenship.” Despite the hardship they had endured in slavery by white Americans, they still wanted to live amongst them and fight under the same country.

The Second American Revolution

The Second American Revolution. Click to expand.

Just as colonial people fought against the British in the American Revolution, African Americans fought against their enslavers and the Confederates in the Civil War. It is often said that the Civil War is “The Second American Revolution” because of the similar fights for freedom, as well as the re-creation of the idea of a Republic and the rewriting of the Constitution. It can be argued that today, the Second American Revolution affects our world more than the first because it prompted absolute equality, whereas the First American Revolution only allowed freedom for white men. Additionally, in the past few years Juneteenth has become recognized by some as “America’s True Independence Day”.

Who was the Republican Party Really For?

Who was the Republican Party Really For?. Click to expand.

The Republican Party at this time supported the end of slavery, but for what benefit? Was it really to help African Americans, or was it in support of a selfish effort? Douglass’ words give us a specific insight which answers these questions. He explains the private intentions of many Republicans: they wished to dispose of African Americans, they did not support Black participation in government and would try to find votes that were not African American. Douglass reveals that, sometimes, even the people who claim to want absolute equality, have different intentions.

Someone to Look Up To

Someone to Look Up To. Click to expand.

Douglass’ claim here is that different groups of people, based on race, country, etc. all have people that they can identify with, look up to, and believe in. During the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction, many Black people served as important figures, including but not limited to, Harriet Tubman who conducted the Underground Railroad; Joseph Rainey, the first Black person to serve in the United States House of Representatives; Robert Smalls, a wartime hero and spokesperson; and Abraham Galloway, a Senator of North Carolina. Among these great leaders was the speaker himself, Frederick Douglass. Through his speeches, books, and actions, Douglass became a figure that gave hope to the people fighting to end slavery. He was adored by many, and the country would not be where it is today without him.

This is our fight!

This is our fight!. Click to expand.

In just a sentence, Douglass is explaining that the upcoming fight for equality will be one that is not fought with “handouts,” therefore it will not be easy. It must be fought by the people and for the people.

Douglass uses A Source!

Douglass uses A Source!. Click to expand.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain alienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” In a great start to this paragraph, Douglass references the Declaration of Independence. He is exposing the hypocrisy of the government, especially those who promote slavery and an unequal system, because it goes against these words that everyone is governed by. Douglass’ next words are even more interesting; differing from the Declaration of Independence as he says that organizations may be created to secure these rights. Douglass knows that the government is not necessarily on the side of enforcing the rights of Black Americans, so he amends the Declaration and instead says that it is an organization’s job to do so. This “amendment” puts more power in the hands of the people, as opposed to the Declaration itself.

A Negative Ending?

A Negative Ending?. Click to expand.

Why did Douglass end this empowering speech on such a negative note? Because it is the truth; there will always be an oppressive class who seeks to tear down a group. Douglass likely ended his speech like this to explain to the people that the fight for absolute equality will be difficult, due to these people, but it will be well-rewarded when it is won.

Page 177: Fred. as Marshall

What is the role of the Marshal of the District of Columbia?

What is the role of the Marshal of the District of Columbia?. Click to expand.

The Marshal of the District of Columbia is in charge of handling prisoners and doing the legwork for the courts and judiciary. The main tasks of the Marshals are to transport prisoners to and from trials, keeping federal judges safe, handling the illegal assets (stolen money, stolen items, etc…) of convicted criminals, and catching fugitives. Before the Civil War the role of Marshal was in charge of capturing fugitives from slavery, ironically Frederick Douglass, himself a former fugitive from slavery, would occupy the post. In his role as Marshal, Douglass, a Black, formerly enslaved man, became a part of the federal criminal justice system. Clearly Douglass taking this role came with a great deal of symbolism. He was the first Black man to get a presidential appointment and be confirmed by the Senate. To many in the country, Douglass’s confirmation as Marshal was a sign of hope that more Black people would be in government positions. While we know today that this hope would not be realized until the latter half of the 20th century, this was not so far from the realm of possibility during the Reconstruction Era. During that time several Black men were elected to be senators and congressmen, giving a glimpse of what Frederick Douglass’s America could look like.

How did others feel about Douglass’s appointment?

How did others feel about Douglass’s appointment?. Click to expand.

There were two main reactions to Douglass’s appointment. On one hand there were mainly the conservatives, with the Democrats on their side, as well as several high-ranking lawyers (and the general opinion of the Bar Association). These people voiced a variety of objections to Douglass’s appointment. Some said he didn’t have a “business capacity,” others said he lacked knowledge of the legal field and of the nature of man, another said that Douglass was too theoretical. According to the Washington Republican, several members of the Bar Association even went before a Senate committee to protest against Douglass becoming Marshal. Yet most of these criticisms rang hollow, and many critics of Douglass’s appointment likely only opposed it on the basis that he was a Black man. On the other side many rejoiced about Douglass’s appointment. They saw it as a great step forward for the nation, and applauded President Hayes on making such a progressive appointment. Many freedmen and abolitionists were also excited about the appointment and many of Douglass’s supporters came to congratulate him in his office. However this initial excitement of fellow abolitionists and radicals would soon vanish.

How did Douglass feel about his appointment?

How did Douglass feel about his appointment? . Click to expand.

Frederick Douglass had a large family, with several children, grandchildren, and siblings. While Douglass was passionate about spreading his ideas of freedom, the post of Marshal allowed Douglass to make enough money to financially support his family, while also giving him more time and space, as well as sparing him from having to go on long tours which were often arduous, and dangerous. Additionally, Douglass saw it as a prestigious and important (as shown earlier) position, and as such he gladly accepted the job; he would keep it until 1881.

What was Douglass’s term as Marshal like?

What was Douglass’s term as Marshal like?. Click to expand.

Douglass’s term was littered with controversy. One of them came when Douglass held a speech about the racism of the citizens of Washington. He mocked the ambitious politicians who only looked to further themselves and their stock, he talked of the white people who had killed Black people before the Civil War, and of racist attitudes that pervaded Washington. This obviously caused backlash from many Washington newspapers (even Republican ones) and citizens who called for Douglass’s removal as Marshal. However, Douglass was also becoming a more complicated figure in the eyes of his fellow abolitionists and radicals who fought for civil rights. In becoming a bureaucrat, some felt that Douglass had lost his radical nature, and that he was no longer fighting hard for equality. To some, Douglass had become a Republican Party functionary, and rarely openly criticized President Hayes’ policies, even though those policies left Black people in the South open to violent attacks, economic exploitation, and disenfranchisement. In general, the Republican Party’s attention had shifted from the rights of Black people to big business interests, for example subsidizing railways heavily and allowing the monopolization of several key industries. Even when Black people fled the South on a large scale in 1879, Douglass kept with the Republican party line, asking those fleeing the violence to simply ‘wait it out’. Philosopher Cornel West has argued that Douglass was "defanged" when he became a Republican party insider. However, it must be acknowledged that Douglass had entered his later stages of life as well as a period of history post-Reconstruction that caused him to change tactics from his earlier radicalism, though he still addressed issues of racism and violence against Black Americans. He also had to worry about his family and supporting them financially.

What was the Washington Sentinel?

What was the Washington Sentinel?. Click to expand.

The Washington Sentinel was a newspaper founded by a German lawyer, Louis Schade, in 1873 which held Democratic viewpoints, and supported the Democratic party. Schade himself later represented a Confederate war criminal during his trial (Schade was unsuccessful, and the war criminal was hanged). However, regarding Douglass’s appointment, the Sentinel is clearly in favor of confirming him. The Sentinel may have done this out of a variety of reasons we can only speculate on. Maybe this is because the paper saw it as a political blunder to oppose it, maybe to frame the Republican party as racist, or maybe on simple moral grounds.

Teacher Resources

Teachers, we hope that this tool can be helpful to you, especially in your education of your students about American History. Using this sheet, your students can annotate their own pages from the Douglass family scrapbooks to further their education on Douglass and the time period of which he lived. We have only been able to annotate these four pages from the Douglass Family Scrapbooks, but there is so much more interesting history in these Scrapbooks to be explored. We believe that the Scrapbooks can provide you and your students with an engaging way of learning about Douglass and Reconstruction, one of the most formative eras in American history. We hope you enjoy!

Google Form: https://forms.gle/1oBY14gSwbY5oUgE7