Mission 66: Modernizing Antietam National Battlefield

Introduction

Antietam National Battlefield Entrance Sign

This digital tour of Antietam National Battlefield focuses on how the National Park Service's Mission 66 program transformed the ways visitors experience Civil War history.

Mission 66 was an ambitious national program to modernize the parks, marking the National Park Service's 50th anniversary in 1966. At Antietam, Mission 66 reimagined the ways people could view, travel through, and learn about the battlefield landscape.

Mission 66 at Antietam NB

Signs for Mission 66 construction along Stevens Canyon Road at Mount Rainier National Park

“This is a Mission 66 Project.” Signs with this message became familiar to national park visitors between 1956 and 1966.

Mission 66 was a program to “modernize, enlarge, and even reinvent the park system” by 1966, the fiftieth anniversary of the NPS. National parks across the country saw a massive increase in visitors after World War II: from 6 million in 1942 to 30 million in 1950 alone. At the same time, maintaining the parks was not a wartime priority. They were in no condition to serve so many visitors. To address this crisis, Congress spent over $1 billion for the expansion of buildings, parkland, and services across the NPS over a decade.

Antietam National Battlefield was one place where the Mission 66 program forever changed how visitors experience the park. Congress established Antietam National Battlefield in 1890 to commemorate the September 17, 1862, Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single-day battle in American History and a major turning point in the American Civil War.

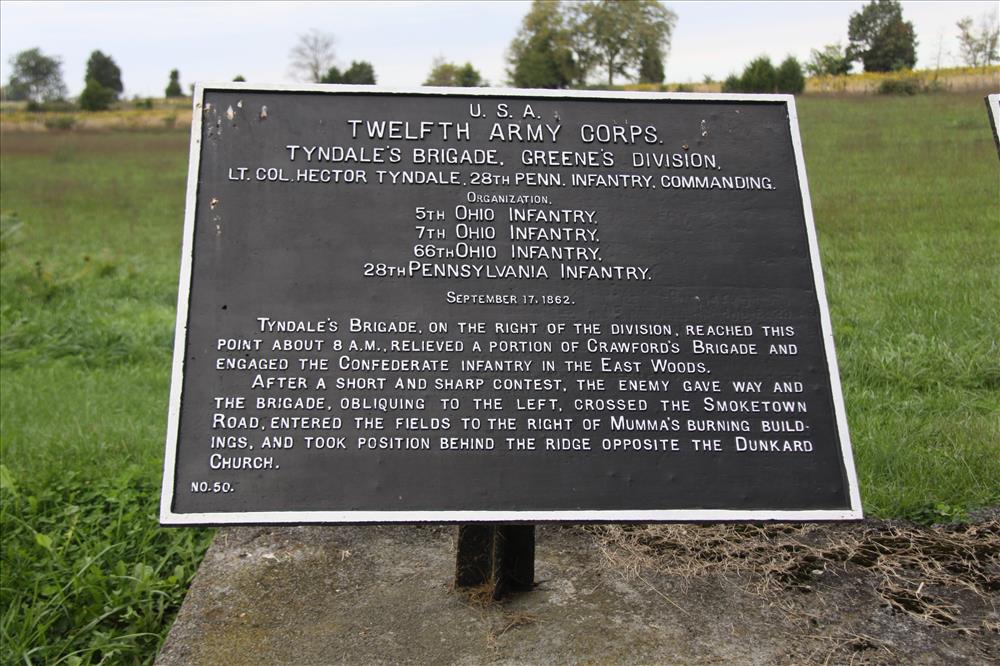

Tablet erected by War Department in 1890s describing troop movements of the Twelfth Army Corps

In the 1890s, the War Department focused on identifying troop movements and important sites, erecting iron signs, and purchasing land for roads. The NPS took over management of the battlefield in 1933. By the 1950s, Antietam faced serious problems: Dunker Church was a ruin, suburban growth threatened the landscape and views, and visitors started their tours in a tiny museum in the Lodge of the National Cemetery.

The Mission 66 program’s vision and funding sparked improvements to the battlefield that were decades in the making. First, Congress passed an act in 1960 (74 Stat. 79) to purchase land to protect Antietam. This allowed the NPS to enlarge the battlefield and cemetery from 195 acres to 790 acres, with an additional 42 acres in scenic easements. This was vital to preserve the site and views of the battle.

Next, the NPS dramatically transformed Antietam from 1960 and 1967. Under Mission 66, the 19th century battlefield gained 20th century roads, interactive exhibits, and preserved and restored historic places. The centerpiece was the Visitor Center: built into a hillside overlooking the battlefield, its architecture is an excellent example of the “Park Service Modern” style created during Mission 66.

Overview Map

The map below shows an overview of the project discussed in this StoryMap. Click on the points to learn about them.

Map of Antietam National Battlefield with points indicating select locations with Mission 66 projects to be discussed on this site

Visitor Center

Antietam National Battlefield Visitor Center

The Visitor Center at Antietam National Battlefield is the centerpiece of the park’s Mission 66 efforts.

With its central location and expansive views of the battlefield, it catered to the modern park visitor. Finished in 1962, it became the cornerstone for car-friendly tours of the battlefield.

Image: The site before construction of the visitor center started

The Antietam National Battlefield Visitor Center is one of more than one hundred new NPS visitor centers from Mission 66. This was a new type of building for the time. It expanded the small national park museums built in the 1930s. It also brought administration and museum services into the same place.

The NPS and architect William Cramp Scheetz Jr. designed the Antietam Visitor Center in the “Park Service Modern” style. Mission 66 introduced this style to reinvent and modernize the NPS.

Image: The Visitor Center when completed in 1962.

Nestled into the hillside, the Visitor Center looks like a one-story building, though it has three levels. The use of long-horizontal massing, flat roofs, minimal ornamentation, and local stone lends it a modern yet minimal appearance on the landscape.

Image: The Visitor Center within the park's landscape today

The glass observation room provides impressive 270 degree views of the battlefield and beyond.

Image: A view of the battlefield from the observation room

Tour Route

Developing a one way automobile tour route was one of the major goals of the Mission 66 program at Antietam. The War Department built access roads through major areas of the battlefield in the 1890s. Mission 66 modernized many of them for automobiles.

Image: Construction of drainage culvert on tour road near Bloody Lane

Today, the Antietam Battlefield Tour Route is an 8.5 mile self-guided driving tour with 11 stops. It takes visitors chronologically through the battle of September 17, 1862.

The NPS added turnouts and overlooks, audio narratives and maps, and roadside markers, new signs, and exhibits along the tour route. These improvements catered toward drivers, providing a new way to experience the battlefield and expanding access to history beyond the walls of the Visitor Center.

Image: Signage for tour stop in front of Harpers Ferry Job Corps at Philadelphia Brigade Park

Providing car access was central to the new vision for the battlefield. The 1957 Mission 66 Prospectus estimated $1.7 million dollars would be needed for roads and trails, out of $2.2 million for the entire program at Antietam.

The tour road is still a popular way to view the battlefield, especially during major events such as the yearly Memorial Illumination.

Image: Vehicles on the tour route at night viewing the annual Memorial Illumination

Dunker Church

Dunker Church

Dunker Church was one of the focal points of the Battle of Antietam. Alexander Gardner’s battlefield photographs made it one of the most recognizable landmarks of the Civil War.

After the congregation moved to a new church in the early 20th century, a violent storm destroyed the building in 1921. By the time the NPS took ownership in the 1950s, all that remained of the original building was its foundation.

Image: Remains of Dunker Church foundation prior to reconstruction

The NPS reconstructed the building in 1961 and 1962 with the help of a donation from the State of Maryland. To be faithful to the past, the project relied on historical research and salvaged materials.

Image: Dunker Church while under reconstruction

The NPS dedicated the reconstructed church on September 2, 1962, in time for the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam on September 17.

Image: Reconstructed Dunker Church

Mission 66 construction also made the church easier to get to. A new brick terrace, walk, and a trail connected it to the Ohio, Maryland, and New York Monuments and the Visitor Center.

Image: View along the Antietam Remembered Trail (originally called the Dunker Church Trail) toward the Visitor Center

The Cornfield

The Bloody Cornfield Sign at Miller Farm

This stop marks the battle in the Miller Farm cornfield. This was the site of more fighting than any other location within Antietam National Battlefield.

The War Department built Cornfield Avenue around 1895. Mission 66 construction created parking and provided information for visitors touring by car.

Image: Construction of audio tour stop at the Cornfield, 1967

The NPS built the parking area along Cornfield Avenue in 1960. Members of the Harpers Ferry Job Corps, a federal work program, built the stone wayside exhibit and sidewalks in 1967.

Image: Cornfield exhibit, c. 1970s

The wayside exhibit allows visitors expansive views north over the D. R. Miller cornfield toward Hooker’s Advance and northeast toward the East Wood and Mansfield Attack. It was built of local stone to mimic the historic stone walls scattered throughout the battlefield. This was one of several new roadside exhibits from Mission 66 at Antietam.

Image: Cornfield exhibit today

Philadelphia Brigade Park

The Philadelphia Brigade Monument stands just outside of the West Woods. The brigade was the third line to move into the woods on the morning of the battle.

This 11 acre park is the site of the Philadelphia Brigade Monument, an obelisk dedicated in 1896 to the brigade’s four regiments. During Mission 66, the NPS rebuilt the entrance road and added parking. In 1967 members of the Harpers Ferry Job Corps built a sidewalk linking the parking area, two stone exhibits, and a trail to the Baltimore (Maryland) Battery monument.

Antietam was one of the first Job Corps sites thanks to Mission 66 construction. President Lyndon B. Johnson began the Job Corps program in 1964 as part of his “War on Poverty.” Its goal was to address rising unemployment, social unrest, and a downturn in the nation’s economy. It was patterned after the successful Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) program of the 1930s. Job Corps recruited young men between 16 and 21 and tried to teach work habits and attitude along with vocational skills.

Image: Members of the Harpers Ferry Job Corps building a stone exhibit at Philadelphia Brigade Park

The Job Corps Training Camp at Catoctin Mountain Park was the first Job Corps site in the nation. It opened in January 1965, and the Harpers Ferry site followed in April 1966. At Antietam, men from the Harpers Ferry Job Corps built exhibits at Philadelphia Brigade Park, the Cornfield, and Bloody Lane.

Image: Plaque commemorating the Job Corps efforts

Richardson Avenue

Modern view of Bloody Lane, also known as the Sunken Road

Bloody Lane (also known as the Sunken Road) is a rutted farm road that served as an important line of Confederate defense during the Battle of Antietam. Many soldiers died in Union crossfire there.

Bloody Lane (also known as the Sunken Road) is a rutted farm road that served as an important line of Confederate defense during the Battle of Antietam. Many soldiers died in Union crossfire there.

The War Department built Richardson Avenue parallel to the historic Sunken Road, or Bloody Lane, around 1895. It added an Observation Tower at the eastern end of Bloody Lane in 1896.

Image: Original locations of Richardson Ave (left) and the Bloody Lane (right)

Mission 66 shifted the paved road away from Bloody Lane to preserve it while making it more accessible to visitors.

Image: Construction along Richardson Ave in 1966

During Mission 66, the NPS removed the original Richardson Avenue, which was too close to the historic road trace, and moved it about 100 feet further south and away from Bloody Lane. The NPS also took this opportunity to widen the road, construct the Bloody Lane Overlook parking area, and create more parking at the Observation Tower.

Image: View of road construction from Observation Tower

The Harpers Ferry Job Corps erected the Bloody Lane stone overlook in 1967. The new overlook provides visitors a place to see the Sunken Road from above. This view dramatically illustrates the close range at which the opposing lines fired at each other.

Image: The protected Bloody Lane road trace

Image: View along Richardson Ave today

Image: View from Observation Tower today

Burnside Bridge

Burnside Bridge

Burnside Bridge is one of the most recognizable places on the battlefield. This bridge that crosses Antietam Creek was the site of a critical action in the battle.

During Mission 66, the NPS transformed the bridge from an active roadway into a peaceful pedestrian historic site.

Image: Construction of McKinley Walk in Burnside Bridge area, 1966

As part of the Mission 66 plan for Antietam, the NPS built the new Burnside Bridge Overlook on the bluff of the west side of Antietam Creek. It offered signs, seating, and views of the bridge and creek below.

Image: Construction of McKinley Walk in Burnside Bridge area, 1966

The NPS also rerouted traffic away from the bridge to help preserve it. With the help of the Bureau of Public Roads, the NPS constructed the Burnside Bridge bypass between 1963 and 1964. This diverted traffic across a new bridge further north, and then connected with the original road south of Burnside Bridge.

Image: Burnside Bridge overlook terrace

Today the “Old Burnside Bridge Road” is for visitor use only. It leads to the overlook and its parking area, where people can stop to visit the exhibit on a ridge above the creek. Visitors can walk down to the bridge and nearby monuments along a path that connects with the historic McKinley Avenue Walk, or hike the 1.8-mile Snavely Ford trail. Across the bridge on the east side of the creek are more monuments and a lower viewing terrace. Next to the terrace is a stone wall along the creek, rebuilt during Mission 66.

Image: Modern photo of section of McKinley Avenue Walk with interpretive signs and benches