A Virtual Tour Along the Dynamic Muddy Creek

A virtual tour highlighting the wildlife, habitats, and dynamic processes that have shaped the backbone of Erie NWR's Seneca Division.

Muddy Creek & the French Creek Watershed

Figure 1. The streams and sub-basins of the French Creek Watershed. The Muddy Creek sub-basin is shown in orange. Credit: USFWS

Muddy Creek forms the backbone of Erie National Wildlife Refuge's Seneca Division, flowing along a 10.5 mile stretch within the refuge. Roughly half of the length of Muddy Creek is located within the Seneca Division. It is also one of 10 major sub-basins (or sub-watersheds) of the French Creek watershed .

The entirety of the refuge lies within the French Creek watershed, which is considered an ecologically significant watershed nationally, and in Pennsylvania, with globally rare freshwater mussels and fish.

French Creek's headwaters begin in southwestern NY, near the town of Sherman, and flows approximately 117 miles, through Erie, Crawford, Mercer, and Venango Counties before converging with the Allegheny River in Franklin, PA (Figure 1).

French Creek is among the most biologically diverse streams in Pennsylvania and the eastern United States, providing habitat to more than 89 species of fish, 28 species of freshwater mussels, and the official amphibian of Pennsylvania, the eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleghaniensis alleganiensis) (WPC 2009).

A Short History of the Land and Its Original People

The area where the refuge lies today was originally populated by the indigenous Erie people, who lived in fortified villages, stored maize among other foods, and tended to the land, using techniques like burning to improve agriculture. It is believed that these native people had relatively little influence on ecological processes or communities in the valley creeks and wetlands of the region.

The map above models the potential vegetation communities that would have historically occurred within the Seneca Division prior to European settlement, and was produced using relationships of vegetation communities to soils, topography, hydrology, and geomorphology. Vegetation communities were primarily comprised of floodplain shrub wetland (cyan), swamp forest (purple), transition forest (orange), and upland hardwood forest (green). Credit: Heitmeyer and Aloia

Following European settlement, the fur trade with European settlers brought the Iroquois Nation to the region, culminating in a war involving the Iroquois (Seneca people) who defeated the Erie in 1655 and caused the Erie to abandon the French Creek Valley. Additional Native American tribes settled in the area as European settlement pushed westward, though these settlements remained sparse due to European disease and continued conflicts.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, European settlements increased throughout the region, with large areas of forests cleared for timber harvest, subsistence farming, and agriculture. Impacts from timber removal included increased rates of soil erosion from cleared hillsides, which caused heavy sedimentation in creek valleys. Over time farming shifted to raising cattle, sheep, and horses as soils were well suited to producing grasses that provided good forage for stock. By the late-1800s the farming population began a steady and slow decline as mechanical farming tools reduced labor and industrial growth increased in cities. Farming continued to decline through the 1900s, with many farmlands being abandoned.

The Creation of the Seneca Division

The lands surrounding Muddy Creek, which make up the Seneca Division of Erie National Wildlife Refuge, were approved for acquisition into the National Wildlife Refuge System by the Migratory Bird Commission in 1967, with the first tracts, totaling 3,027 acres, being purchased in 1973. Today, the Seneca Division consists of 3,753 acres, much of which is wetland or forested habitat, but also contains abandoned crop, hay, pasture, and orchard lands. The conservation of these lands provides refuge for hundreds of species, while also forming a forested buffer that protects Muddy Creek and its tributary streams, wetlands, and other aquatic resources from development, habitat fragmentation, and habitat degradation.

Muddy Creek gets its namesake from its muddy, brown-colored waters. Credit: USFWS

The Waters of the Muddy Creek Sub-Basin

It is believed that Muddy Creek received its namesake due to its "muddy" brown waters. This color is created as the creek meanders along highly erodible exposed soil streambanks, which create the turbid characteristics of the stream. This trait, however, is increasingly influenced by land use activities upstream, which have influenced Muddy Creek and its water quality.

Though recent assessments have not identified any acute water quality issues within Muddy Creek, the turbidity of the creek has increased over time, as documented by water quality monitoring of Muddy Creek and its tributaries (Patnode 2012) . This is mainly caused by farming and grazing practices, which increase sediment loads and agricultural fertilizers (or excess nutrients) entering the creek and its tributary streams. One upstream tributary of Muddy Creek has also been listed as impaired by the EPA due to siltation from these practices.

Other inputs such as salt and brine applied to country roads may negatively impact surface water and infiltrate the soil, thus impacting plant growth, and/or the quality of water and sediments in wetland areas throughout the Muddy Creek basin.

To learn more about why the Refuge monitors water quality, click the following link to be directed to our StoryMap's Research & Monitoring chapter .

A Crash Course in Stream Ecology

A Tour along the Dynamic Muddy Creek

Geology & Geomorphological Processes

Fluvial Features: Meanders & Oxbow Lakes

The Importance of Large Woody Debris

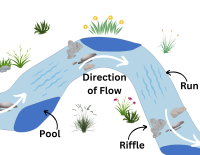

Stream Anatomy - Riffles, Runs, and Pools

A Story of Wetlands

Emergent Herbaceous Wetlands

Wet Shrublands

Forested Wetlands

Recreational Opportunities

Freshwater Stream Ecosystems

Freshwater stream ecosystems in northwest Pennsylvania are diverse and dynamic, supporting a rich array of aquatic life. These ecosystems are characterized by a variety of physical and chemical factors, including water flow, temperature, and nutrient levels. The food webs within these streams and surrounding wetlands are complex and interconnected, showcasing the interdependence of different organisms.

The diagram above displays the organisms one might encounter in a typical freshwater stream in Northwest Pennsylvania.

At the base of the food web are primary producers such as algae, diatoms, and aquatic plants, which use sunlight to convert energy into organic matter through photosynthesis. These primary producers form the foundation for the entire ecosystem. Equally important are the decomposers, including fungi and bacteria, which breakdown decaying plant and animal material, recycling nutrients back into the system. Herbivores, including insects and small invertebrates feed on the primary producers, while serving as prey for larger organisms.

Streams are inhabited by a diverse range of fish species, including brook trout, American pickerel, various minnows, and darters. These fish play a crucial role as both predators and prey, contributing to the overall balance of the ecosystem. Aquatic insects, such as mayflies, caddisflies, and stoneflies, are abundant and form a significant portion of the diet for many fish species.

The food web also includes secondary consumers, such as larger predatory fish, turtles, amphibians, and water-dwelling insects. Birds, like kingfishers and herons, are common predators in these ecosystems, feeding on fish and aquatic invertebrates. Terrestrial organisms, like spiders and beetles, also contribute to the food web when they fall into the water.

In the sections below, we will highlight many of the organisms one might encounter in the wetlands and streams of the Muddy Creek basin, touching upon several aquatic plants, macroinvertebrates, mussels, fish & more !

Aquatic & Wetland Vegetation

Highlighted below are some of the aquatic and wetland vegetation species found within the Muddy Creek basin.

Aquatic Macroinvertebrates: Stream Bioindicators

Aquatic macroinvertebrates are insects in their nymph or larval stages, snails, worms, and crayfish that spend at least part of their lives in water. Macroinvertebrates are named as such because they are large enough to see without a microscope.

Aquatic macroinvertebrate communities are strongly influenced by their surrounding environment, and act as bioindicators for the overall condition or health of freshwater ecosystems.

Macroinvertebrates play a key role in aquatic food webs as they are primary processors of organic materials, recycling nutrients back into aquatic systems. Some studies have suggested that aquatic macroinvertebrates are responsible for processing up to 73% of the riparian leaf litter that enters a stream (Covich et al. 1999). They are also major food sources for higher trophic levels. Macroinvertebrates are often food generalists and have therefore been classified into groups called functional feeding groups.

The 5 major functional feeding groups are:

A mayfly larva, of the Order Ephemeroptera found in Woodcock Creek. The mayfly larva are an example of a collector. Credit: USFWS

- Scrapers (or grazers), which consume algae and associated material. Grazers are found on rocks and woody debris. Included in this group are water beetles and snails.

- Shredders, which consume leaf litter, woody debris, and other coarse particulate organic matter (CPOM). Included in this group are caddisflies, crane flies, and stoneflies.

- Collectors (gatherers), which collect fine particulate organic matter (FPOM) from the water column and stream bottom. Included in this group are true flies, mayflies, crayfish, clams, mussels, and aquatic earthworms.

A dark fishfly larva, of the Genus Nigronia. Dark fishflies are an example of a predator. Credit: USFWS

- Filterers, which collect FPOM from the water column using a variety of filters. Included in this group are blackflies and net spinning caddisflies.

- Predators, which feed on the 4 feeding groups (consumers) listed above. Included in this group are stoneflies, dragonflies, damselflies, dobsonflies, water beetles, and leeches.

In the interactive screen below, hover above groups of freshwater macroinvertebrates to learn more about individual species and their diagnostic characteristics!

Credit: Macroinvertebrates.org

The Crown Jewels of Muddy Creek are its Abundant & Diverse Aquatic Life

A diverse assemblage of aquatic organisms found within the Muddy Creek watershed, in order from left to right: Mottled sculpin (Cottus bairdii), a Cambarid crayfish (Family Cambaridae), Fatmucket mussel (Lamsilis siliquoidea), Logperch (Percina caprodes), and Rainbow darter (Etheostoma caeruleum). Credit for Images 1, 3, 4, & 5: Alejandra Lewandowski; Image 2: USFWS.

A collage highlighting several of the freshwater mussel species found within Muddy Creek. Credit: Y. Laskaris/USFWS

The portion of Muddy Creek that flows through the Seneca Division provides habitat for 22 species of freshwater mussels, including the federally endangered Northern riffleshell, rayed bean, snuffbox, clubshell, the federally threatened rabbitsfoot and longsolid, and several state-listed and globally rare species. Muddy Creek appears to be second only to the main stem of French Creek in providing habitat for the most diverse assemblage of freshwater mussels in Pennsylvania (WPC 2004).

There are 60 species of fish found in Muddy Creek and its tributaries. These include at least 45 species reported to serve as freshwater mussel hosts, and two of 34 Pennsylvania state-listed fish species (Haynes and Wells 2006, PFBC 2018). These host fish species are critical to the successful reproduction of many of the rare freshwater mussel populations, carrying the mussels’ glochidia larvae during a critical development period (Haynes and Wells 2006). Many of these host fish are darter species, including the rare eastern sand darter which was rediscovered in 1991.

DID YOU KNOW? Freshwater mussels are the most endangered group of organisms in the United States. Of the 303 species known to exist in North America, over 70% are considered endangered, threatened, or of special concern.

Mussel Life Cycles & Life History Strategies

A diagram of the lifecycle for freshwater mussels showing how larva from a fertilized adult female needs to use a host (fish gills) in order to metamorphose or transform into a juvenile adult. Without this parasitic stage juvenile, thus adult mussels would not be created. (John Megahan/University of Michigan)

Awe-Inspiring Adaptations

One of the most fascinating things about freshwater mussels are the variety of life history strategies mussel species have evolved to attract host fish to take up their larva. To get their glochidia into a fish's gills, mussels require luring fish hosts close to their bodies. Many species have evolved lures that mimic food items that host fish are attracted too, including minnows, crayfish, flies, and worms.

Other species, like members of the Genus Epioblasma, which includes the snuffbox (Epioblasma triquetra), have evolved to clamp their valves shut on the heads of fish that mistake them for stones while searching for food items on the stream bottom.

Some species, like the scaleshell (Leptodea leptodon), even go so far as to sacrifice their lives for reproduction, by unburying themselves, lying on the top of the substrate, and offering their bodies on a silver platter to be eaten whole by fish. In this extreme example, the fish chomps down on the female, and the larvae the female was holding inside are then released into the fish's gills.

A largemouth bass attacks a Plain Pocketbook (Lampsilis cardium) displaying it's mantle lure, which strikingly resembles a minnow. Contact with the female mussel's mantle lure triggers the release of hundreds of juvenile larvae (glochidia) into the gills of the unsuspecting bass. Video by Brett Billings and Ryan Hagerty/USFWS.

Can't get enough of the amazing lives of freshwater mussels?!

Click the links below for additional information on freshwater mussels, their ecological and cultural value, evolutionary relationships with fish, and the enormous biodiversity of species found across North America.

The stories below highlight habitat restoration efforts, and the work performed by National Fish Hatcheries to raise and stock freshwater mussels to be released as part of population recovery. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is also collaborating to 3D print freshwater mussels for research and education!

Wetlands Supporting Wildlife

Research & Monitoring

The Refuge performs several inventory and monitoring projects to understand the health of forests, streams, wetlands, and the wildlife populations. Use the slideshow below to learn more about some of these projects!