Historic Environment and Climate Change in Wales

Wales as a nation shares a cultural inheritance over thousands of years. The layers of this history can be read in our landscapes and townscapes, and in the countless historic buildings and ancient monuments that are all around us. It is seen in the chapel, the working man’s institute, our homes and the local park. Patchworks of farms, fields and woods, rough grazing and rich pasture, towns, cities and villages all make up a rich historic landscape - Wales.

We may not notice it as we go about our daily lives, but the historic environment is constantly changing and evolving through natural processes and human actions. Managing these changes helps us to protect the things we value.

But we are now facing the greatest challenge of all, from climate change. This will alter our landscapes and our historic places.

The Welsh Government declared a climate emergency in April 2019 and we are committed to taking steps to limit climate change. Nevertheless, its impacts are already being felt on the historic environment.

Warmer temperatures, rising sea levels, changing rainfall patterns and more frequent extreme weather events are now familiar. The impact of these effects on our historic assets, which are irreplaceable, will have significant consequences for the historic environment as a whole as well as the people of Wales.

We have already seen the major impacts of flooding and coastal erosion on some of Wales’s historic settlements, their residents and local economies.

There are also likely to be longer-term and less direct impacts that we cannot yet predict or understand fully. We need to respond to these challenges and opportunities by considering what we can do and how we can adapt now, and in the future.

Adaptation means changing the way we manage and look after sites, places and landscapes to take account of future changes in climate. It is the process of adjusting to actual or predicted climate change and its effect.

Adaptation can be proactive or reactive, but should be thought about long-term. Changing management regimes, for example, and improving drainage around historic structures can be a way of making them less vulnerable to extreme weather events. Reactive adaptation could include repair and restoration or even re-location.

Sometimes adaptation means recognising that a particular site will be so severely damaged by the effects of climate change that the only practical response is to recover as much information as possible before the site is lost.

The Historic Environment Group has prepared an Adaptation Plan , to help us all respond to the impacts of climate change. There are also a number of case-studies, showcasing different approaches.

Case Studies

The map below indexes a number of case studies, showing different ways of adapting to a changing climate. Each entry has a link to a more detailed description. Clicking 'back to map' on each entry will return you to this index.

Over time, more case-studies will be added to the map

Bathrock Shelter

Plas Newydd

Forest Resource Plans

Dinas Dinlle

Waun Fignen Felen

Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal

Fron Goch Lead Mine

Plas Cadnant

Twmbarlwm

Caerwent Meadows

St Patrick's Chapel

Bwlch y Ddeufaen Roman Road

"Bronze Bell" shipwreck

St Michael's Church, Llanfinhangel y Creuddyn

Pembrokeshire Coast's Monuments

Lake Vyrnwy Peatland Restoration

Data Gathering and Understanding across Wales

In order to adapt to a changing climate, land and property managers need to be able to make reasonable predictions about what the impacts of the changes may be. This means not just modelling what climatic conditions may be in the future, but also how different types of buildings and structures will respond to it.

Domestic Dwellings in Wales

Climate change is not just increasing the risks to the fabric of buildings but also to the health and comfort of the building's occupants due to changes in indoor air quality. The quality, design and operation of buildings across the UK must therefore be improved to address the challenges of higher temperatures and more variable rainfall. This is particularly true in Wales, which has a high proportion of older housing.

In 2021 Cardiff Metropolitan University, in collaboration with the University of Colorado and Resilient Analytics, conducted climate vulnerability modelling of domestic buildings in Wales. This aimed to find out more about the risks climate change posed to different types of domestic dwellings.

The findings of the report highlight both the strengths and weaknesses of traditional housing stock and newer construction types - meaning that building owners are better informed and will be better able to alter internal fit-outs, use alternative building materials, adopt appropriate building cooling and ventilation strategies and adapt their behaviours in response to climate change.

The full report can be read here.

Climate Hazard Mapping

As a major landowner, The National Trust knows that the effects of climate change will impact on their land and properties. To adapt, the Trust needs to understand present climate hazards and consider those it may face in the future. These hazards translate into vulnerabilities and possible impacts not only to the Trust’s land and properties, but also on its own activities and those of others who use the National Trust’s sites and resources.

To achieve these insights, the National Trust identified the need to bring together a variety of different data-sets highlighting different risks associated with climate change impacts. The challenge is that many of these data-sets were developed independently of each other and not designed to be viewed through a single portal.

Working with a range of consultants and partners, the National Trust Climate Hazards webmap was developed. This is based on difference mapping - answering the questions "What are climate factors like today?" and then "what will those factors look like in 2060 in a worst-case scenario?". This allows site managers across the UK to see predicted impacts for their areas and develop appropriate adaptation.

More details on each of the mapped case studies are given below. Or you can return to the map here

Aberystwyth - Bathrock Shelter

In early January 2014 a series of storms battered Aberystwyth Promenade. Many structures were severely damaged, including the grade II listed Bathrock Shelter, which dates from the 1920s. The storm and resulting turbulent sea, combined with very high tides, breached the bastion on which the shelter sat and revealed the footings of an earlier bathhouse, associated with the Marine Baths built by Doctor Rice Williams Esquire in 1810. Loose material used as fill for the bastion was washed away and the resulting void led to the partial collapse and subsidence of Bathrock Shelter.

Left: Bathrock shelter damaged by a storm in 2014. Right: the remains of the bathhouse that were revealed beneath the shelter

Adaptation saw the consideration of the overall significance of the shelter and the role it plays in the character of Aberystwyth's sea-front. The decision was taken to re-instate the feature, so it was carefully restored by Ceredigion County Council. Emergency recording, including detailed photography, was carried out by the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales so that there is a permanent record of the original structure.

The restored structure is built over a strengthened and re-engineered sea wall, making it more resilient to future storm events.

Plas Newydd

Plas Newydd is a grade I listed building and Accredited Museum sitting within a grade I registered historic park and garden. There are other listed structures and a scheduled monument, the Plas Newydd burial chamber, within the grounds. On Boxing Day 2015 Anglesey experienced high winds and rainfall. Flood water found its way into the basement where the mains electric switch panel was located. Water was waist deep and although none of the collection or building fabric was seriously harmed, the mansion’s electricity supply was damaged irreparably. As a result, the mansion was without full power for a period of four weeks, staff flats had to be vacated and a private security firm employed while the building was unoccupied. As a temporary measure, sand bags were put in place to divert flood waters into a drain, the cover for which has since been replaced with a grille. In November 2017 another, more severe, storm occurred. On this occasion, however, there was more extensive wind and water damage to the gardens around the mansion with landslips resulting in the loss of paths and storm damage to trees.

Left: water penetrating the cellar areas. Middle: Damage to the paths. Right: Flood water being channelled along the ha ha.

Adaptation: A more robust emergency plan has been implemented, the mains electricity switch panel was relocated and the drainage and maintenance regimes were reviewed to improve flood/storm alleviation and defence measures. The effectiveness of this plan was demonstrated in November 2017. Although flood water once again entered the basement, and worked its way into the house itself, the emergency plan ensured that the power was switched off before the supply could be damaged. Following the November storm, a more detailed survey has been undertaken to look at further options for flood alleviation and defence measures. Management of a shelter belt on neighbouring land has also been discussed to help prevent further wind damage.

Waun Fignen Felen

As well as being important for biodiversity, bogs are also important archaeologically. The water-logged and oxygen-free environment can preserve organic material for thousands of years. This means that evidence of past environments can be recovered - pollen and plant remains, for example, which allow archaeologists to reconstruct the flora and fauna of an area. Textiles, wood and leather can also be preserved, which are rarely seen in other archaeological sites. Occasionally bogs can also hold animal or human remains in excellent states of preservation.

Waun Fignen Felen is an upland bog, and a significant Mesolithic archaeological site. It is a place used over several millennia as a hunting location by populations exploiting the uplands. Finds made there include tools and artefacts as well as charcoal and evidence of the past environmental conditions.

Waun Fignen Felen has been slowly drying out throughout the twentieth century, but the effects of climate change has sped the process up. The drying means that the ground surface is not covered in vegetation, and the exposed peat is quickly eroding away. Standing, isolated columns of peat (known as 'haggs') identify the height of the original bog surface, and the bare peat demonstrates the effects of ongoing erosion.

Left: peat erosion channels, contrasting with the ongoing conservation restoration work within the site. Right: haggs and eroding peat fans at Waun Fignen Felen.

Adaption: The Brecon Beacons National Park Authority and the Waun Fignen Felen Management Forum are working to improve the area. Blocking gullies and drainage channels has slowed the erosion and water run-off, and allowed the water table to rise again, helping to keep the bog wet.

Long-term management of the area aims to conserve its biodiversity, its archaeological significance and paleoenvironmental values. Managing the water table and protecting the peat from drying out and eroding will help the area withstand future impacts of climate change.

Dinas Dinlle

The scheduled monument of Dinas Dinlle is a dominant hillfort lying on the north Gwynedd coast on the top of glacial moraine, designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest for its geological significance. The site has been subject to extensive erosion. The impact of heavy rainfall, as well as wind and wave action during storms has resulted in over 50 metres of the western side of the monument being lost since 1900. The outcomes of climate change will lead to more rapid erosion of the monument, which could be entirely lost over the next few centuries.

Adaptation: The monument is owned by the National Trust and their Coastal Adaptation Strategy involves ‘embracing the inevitable’. Whilst no active intervention is planned to stop erosion, a series of adaptive actions are taking place, including the construction of wooden pathways to control erosion and a fence along the edge of the cliff, plus the repair of other footpath erosion.

Recognising that the site will eventually be lost, archaeologists have been working to understand it better and record as much information as possible,

New research led by a team of archaeologists, surveyors, geographers and scientists from the European-funded CHERISH Project began in 2017.

This has included survey of the eroding cliff face, a programme of geophysical survey and archaeological excavation.

The latter resulted in the discovery in 2019 of two sides of a well-preserved stone structure, buried under sand. The structure is interpreted as a round house approximately 13 metres in diameter, with stone walls surviving 3 to 4 courses high and 2.4 metres wide. A possible second round house was identified to the south.

With support from Cadw, the National Trust’s Neptune Fund and CHERISH, a substantial roundhouse was chosen for consolidation and display.

Gaps in the roundhouse wall were reinstated, saved turf was used to plug gaps and create a soft topping. Stone pitching was added to the entrance to guard against foot erosion and protect the deposits beneath, which were left in situ. A certain level of back filling and landscaping was undertaken with excess spoil being removed and used to fill in erosion scars elsewhere on the site.

Biodegradable erosion control matting was used to support areas around the roundhouse, and these were re-seeded. Interpretation boards will be installed which draw on the various strands of research work undertaken and raise awareness of the present and future impacts of climate change at the site.

Dinas Dinlle Animation

Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal

The Monmouthshire and Brecon canal, opened in 1812, runs through the Brecon Beacons National Park. Over the winter of 2013-14 excessively heavy rainfall led to 125 metres of the embankment alongside the canal near Llanfoist moving, dropping downwards and causing a long tension crack. There was also a landslip nearby, putting three properties at risk at the base of the embankment.

Investigation showed that the heavy rain had caused the slip - it had totally saturated the soil, making it move and slide against the bedrock underneath. As a result, the embankment had settled along its weakest points, the lining of the canal.

Left: Ground slumping away from the concrete lining of the canal near Tod’s Bridge. Right: Repairs to the embankment near Llanfoist

Adaptation

The damage to the channel lining meant that the canal had to be closed and drained. Repairs were a huge engineering operation, filling the crack and securing the embankment to the bedrock using soil nails up to 19 metres long, netting and structural plates. The tow-path was re-instated.

Similar problems will be avoided at other sites by concrete lining vulnerable embankments, which will also reduce leakage and therefore water demand, or by rebuilding with a reinforced earth structure, depending on circumstances. New research is also being carried out, to help predict how climate change will affect this sort of structure and to model how to avoid catastrophic failure and costly repairs.

Forest Resource Plans

The Cwm Einion and Upper Rheidol forest resource plan covers an area of 2,371ha.

The area is home to a number of important archaeological features, including ruined buildings, tracks and mineshafts which are testament to the once-crucial lead mining industry which shaped the area. Some of these remains support the growth of rare lichens which thrive in the mineral-rich environment.

Ruined buildings and spoil tips, like these at Esgair Hir, are important archaeological sites in their own right as well as being home to rare lichen and plant species

Climate change means that this area is facing a number of challenges including wildfires and invasive species like rhododendron and Japanese Knotweed. High winds and storm events make the trees more vulnerable to windthrow, which can damage or destroy archaeological remains, and clearing windblown and vulnerable trees requires vehicle access and infrastructure to sensitive areas.

Wildfire at Cwm Rheidol, 2018. Warmer, drier weather makes wildfires more of a threat, causing damage to both biodiversity and archaeology as well as threatening homes and livelihoods.

Adaptation

Adaptation is taking place at both a small and a landscape scale; guided by Forest Resource Plans. These plans set out management actions for each archaeological site, according to their significance and their vulnerability.

At a landscape scale, the resilience of the woodland is being improved by being planted with a more diverse range of species, selected to withstand the impacts of climate change. Invasive species are being removed or managed along the Einion Valley. At a small scale, individual sites are being managed to maintain micro-climates which are as stable as possible, to allow rare lichens and plans to continue surviving as well as keeping archaeological features in good condition.

Fron Goch

Wales has around 1,300 abandoned metal mines and these have left distinct marks on the landscape; many cause pollution to rivers and streams. Wetter winters and more frequent extreme weather are likely to increase pollution and therefore mitigation and adaptation measures are essential, for example, as seen at Frongoch metal mine near Aberystwyth. Frongoch was once one of the largest lead and zinc mines in mid-Wales employing over 300 miners at its height in 1881.

Adaptation: Work by Natural Resources Wales to tackle pollution from the mine was completed in June 2015 at a cost of £1.15 million. It included diverting streams away from the mine and capping contaminated mining waste with soil and clay. This work was undertaken in close collaboration with archaeologists to record and conserve the archaeological remains where possible.

Archaeological excavation and recording of a buddle at Frongoch. A buddle formed part of the process of recovering metal ore from waste.

Plas Cadnant

Prolonged rainfall caused flooding within the historic garden of Plas Cadnant in December 2015. As field drains blocked, overland flow was funnelled into a natural valley, sweeping away paths, damaging plants and causing the collapse of the south wall of the large walled garden.

Left: Plas Cadnant walled garden following flooding. Right: Adapted replacement stone wall at Plas Cadnant.

Adaptation: The site has been reinstated, with historic features being carefully reconstructed with adaptations to prevent damage in case of future flood events. The former gravel paths have been re-laid with tar and chippings, and the nineteenth-century stone wall has been re-built with a reinforced concrete core, clad with stone. Two flood holes have been designed into the base of the wall, in order that in any future floods the water is able to pass through the wall without causing structural damage.

Twmbarlwm

During the hot summer of 2018 a series of wildfires swept across the archaeological site of Twmbarlwm, burning through the vegetation and turning the soil to dust. This iconic site has earthworks from the Bronze and Iron Ages and is crowned by the remains of a motte and bailey castle, built in the 13th century. Following the fires, initial inspections suggested that in places the burning had been severe enough to destroy all organic material in the soil, meaning that natural regeneration of the vegetation was unlikely. Without a covering of vegetation the site was vulnerable to erosion caused by wind and rain, threatening archaeological features and deposits. There were also concerns that buried archaeology could have been damaged by the intense heat of the fire, particularly in the areas where the soil had been badly burnt.

Swipe the image to see the extent of the burning following wildfires in 2018

Adaptation: Cadw and the Twmbarlwm Society, a local volunteer-run organisation, began a project to assess the damage caused by the fires and design a longer term management programme to increase the resilience of the monument. Initially they tried to reseed the burnt areas of the site in the hope that the grass would start to grow and stabilise the ground surface before the winter storms set in. Unfortunately, just as the seed had started to grow south Wales was hit by the first severe storm of the autumn and the heavy rain and strong winds resulted in most of the seed (and a lot of the exposed soil) washing away.

Left: archaeological excvavation on Twmbarlwm Right: scattering grass seed to try and re-establish a grass cover and prevent erosion

An archaeological excavation took place in 2021 (delayed by weather and Covid). It aimed to find out the impacts of the fire and better understand the archaeology on the site. Very little is known about the monument which makes it difficult to make decisions about the best way to manage it and ensure its future protection. The excavation showed that, fortunately, the fires had not burnt deep enough to impact on the buried archaeology. It revealed that the monument defences consist of a large rock cut ditch and stone bank. Charcoal was found in the ditch which should give a date for the ramparts.

A grassland management plan was drawn up, to reduce the potential of such intense wildfires in the future. The plan recommends reducing the amount of flammable material, such as bracken, tussocky grass and bilberry across the hill over a 10 year period through a combination of improved management (cutting and clearing) and increased grazing. This will have the added benefit of opening up the hillside to more diverse species of plants and increasing biodiversity.

This kind of grassland management is also being used on other archaeological sites in order to make them less vulnerable to wildfires. By ensuring that the grassland is kept open, and that species like bracken are not allowed to dominate, there is less fuel for wildfires making them less intense and damaging. As hotter summers become more common, and the potential for wildfires increases, this kind of management is crucial in adapting to the effects of climate change.

Caerwent Meadows

Caerwent Meadows is a volunteer-led community organisation which has taken over 11 acres of land within Caerwent Roman Town. The areas include key Roman buildings and features - the remains of the amphitheatre, villas and other significant buildings, together with a section of the impressive, above-ground Roman Town Walls. The land had been under-grazed for a number of years, allowing invasive species and scrub to thrive, including ragwort, hogweed, bramble and nettles. With warmer overall temperatures and longer growing seasons, the proliferation of scrub was increasing, masking the above-ground archaeological remains and causing root damage to the below-ground remains.

Adaptation: Caerwent Meadows took over the management of the fields in spring 2020 and have developed a 5 year strategy to create sustainable wildflower meadows. These will be a facility for local residents and visitors, as well as a wildlife-rich, visually appealing, biodiverse environment that will ensure the protection of the buried and upstanding archaeology.

The overall aim is to create more bio-diversity and to increase the resilience of the area to extremes of climate. Well-managed pasture holds water, reducing the potential for damage caused by run-off and flooding, whilst the removal of diseased trees reduces the risk of storm-throw causing severe damage to buried archaeology.

Different management regimes are being tried and carefully monitored in different areas, in order to provide detailed data about meadow development and to inform the management of meadows elsewhere.

Top left: clearing bramble and scrub. Top, centre: sowing wildflower and meadow grassland seeds. Bottom, left: the development of species-rich grassland, building resilience and improving the condition of archaeological remains. Bottom, centre and bottom, right: monitoring and recording data from different management methods to inform meadow management elsewhere

St Patrick's Chapel

Excavation at St Patrick Chapel, showing its proximity to the beach and vulnerability to erosion

Situated just behind the beach at Whitesands Bay, the Scheduled Monument of St Patrick's Chapel comprises the buried remains of a chapel and cemetary. The site has long been known about and, at intervals, heavy storms and high seas have made incursions into the cemetary, uncovering human remains. However in more recent years the damage has been more regular and more severe. The last attempt to protect the site, in 2014, failed when the heavy boulders placed there were washed away in a severe storm and burials inside the cemetery were exposed.

The remains of the chapel exposed by excavation

Adaptation. Previous attempts to protect the site from the sea had only been succesful short term, and it was clear that this was unsustainable. Preservation by record seemed the best approach, but the significance of the site meant that great care had to be taken to recover as much information as possible, using a variety of archaeological and scientific techniques.

Between 2014 and 2016, the Dyfed Archaeological Trust and the University of Sheffield worked with the landowners, the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority, to excavate the site and retrieve as much information as possible.

Burials exposed during the excavation

A further season of excavation took place in 2019 as part of a European funded project called 'Ancient Connections'. The excavations have shown the importance of the site, revealing over 100 burials ranging in date from the eighth through to the eleventh centuries. Research into the skeletal remains has allowed archaeologists to find out about the individuals buried here - including their diets and backgrounds. The individuals include men, women and children of all ages.

The excavation was assisted by an army of volunteers and, in addition, hundreds of visitors came to view the excavation which was also seen on local and national television. Exhibitions, publications and websites also shared the story. This publicity helped to raise awareness of the impacts of climate change on historic sites and showcase the significance of local archaeology.

The results of the excavation have enabled the National Park Authority to improve the interpretation of the site, allowing visitors to the popular beach to learn about its history.

St Patrick's Chapel 10 minute video in English

Information from the excavation was used to produce this reconstruction of St Patrick's Chapel.

Bwlch y Ddeufaen Roman Road

The Roman road between the legionary fort and town at Chester and the important auxiliary base and seaport of Segontium, Caernarfon, crossed the mountains of northern Snowdonia through the pass of Bwlch y Ddeufaen. The road runs through an exceptionally rich archaeological landscape, including a Neolithic burial chamber, Iron Age roundhouses and field systems and Medieval settlement. Until rail and road routes were engineered along the coast, this road across the mountains remained an important transport link. Today it is still used - by local farmers and landowners for access, and for leisure use by walkers, horse-riders and cyclists.

In the high ground of the mountain pass, there are clear sections of well-preserved Roman Road surviving. As a sunken track, the road funnels water draining down from the mountain; historically this was managed by a careful system of side ditches and culverts, some covered with stone slabs. Increasing storminess and heavy rainfall has meant that there is more water flowing than the drainage can deal with, creating ruts and potholes in the track's surface. Water flowing down towards the village of Rowen has also caused destabilisation and collapses on a public road.

Water channelled down the Roman road, causing further damage to its surface and threatening flooding and collapse of roads below it.

Adaptation. The Snowdonia National Park Authority, Conwy County Borough Council Highways Department and Cadw worked together during the winter of 2020/21. Significant lengths of side ditch were cleared of silt, culverts were cleared and damaged portions of track repaired and re-surfaced with cobbles and shale. The track should now be able to cope better with peak water-flows, with as much water as possible being carried across its surface and into the drainage systems alongside the road, rather than down it and into the village below.

There is more work to do, but it is hoped that after more repairs the track will be maintained through a rolling programme of small-scale works, carried out in conjunction with local landowners. The works mean that the track remains accessible, its historic features are maintained and future damage to the public road in Rowen is avoided.

"Bronze Bell" wreck site

Some of the marble blocks on the sea-bed

Discovered in 1978 and subsequently designated as a protected wreck, the "Bronze Bell" wreck lies in around 8m of water on the Sarn Badrig reef. The wreck's name is unknown, but it is likely to be the wreck of a Genoese merchant vessel lost in 1709 with a cargo of marble blocks. A bronze bell, dated 1677, was found on the wreck.

The wreck has been periodically monitored since its designation, but climate change has the potential to increase damage to the site through:

- increased storminess and water turbulence causing physical damage

- changing pH levels (mostly acidification) affecting the preservation of metal objects

- increasing water temperatures allowing the spread of Shipworm (Lyrodus pedicellatus) - a wood-boring species which can affect wreck sites

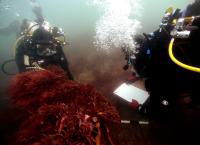

Divers recording the wreck site of the "Bronze Bell"

Adaptation. In 2021, as part of the CHERISH programme, the site was comprehensively surveyed using a variety of different techniques. Photogrammetry allowed the production of a 3D plan of the wreckage on the seabed, and divers were able to photograph the wreck and produce a new ground-plan of it. This was compared to previous plans, and new archaeological evidence identified.

Environmental evidence was also collected, to allow future monitoring of the waters surrounding the wreck, and the impacts that the changing climate is having on it.

This level of comprehensive monitoring and recording sets the standard for future underwater recording of historic sites. It also allowed the team to engage with the public, through talks, online dig diaries and films; raising awareness about the vulnerability and significance of underwater archaeology.

St Michael's Church, Llanfinhangel y Creuddyn

Climate change is increasing the risks to building fabric, and at the Grade II* Listed medieval church of St Michael’s in Llanfihangel y Creuddyn, Ceredigion increased rain led to water ingress through the church tower into the main body of the church and caused serious problems of damp. The water ingress affected the church electrics, and this, combined with an ineffective oil heating system - the boiler of which was housed in the church tower and added to the damp issues due to the condensation it created - resulted in the church having to close in 2017 for the safety and health of the congregation and visitors.

Adaptation:

The local community care greatly about their church and came together to initiate a community project to undertake repairs and improvements to futureproof the church. They raised money and successfully applied for funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the National Churches Trust, the Wolfson Foundation, the Headley Trust and Ceredigion County Council.

Between 2019 -2023 repair and improvement work was undertaken. This included removal of cement pointing, and the repointing and parging in hot lime (the same type of breathable material used in the original construction) of the south and west faces of the church tower - those ones which bear the brunt of the weather. Here, new deeper leadwork was also inserted.

Inside the church tower extensive repairs were made to the tower floors. The ends of some of the 500-year-old floor beams had started to rot where they were embedded in the damp, wet tower walls. These sections were cut out and replaced with new oak sections before new oak floorboards were laid. The new floors were then able to take the weight of a new stair providing safe public access up the remarkable medieval tower to its ancient belfry.

The old oil heating system was removed, the church rewired and is now heated and powered with green electricity. The church reopened in summer 2022.

Work was undertaken on the exterior of the church tower, during the summer and autumn 2021. © Louise Barker

Pembrokeshire Coast's Monuments: a citizen science approach

In 2020, the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority (PCNPA) established a volunteer monitoring programme for publicly accessible scheduled monuments. A total of 17 heritage volunteers were recruited and trained to visit allocated sites and submit information on identified issues via an online system called Survey123. This system allowed volunteers to record the extent of issues and submit photos. In total, 128 monuments are monitored, accounting for almost half of all scheduled monuments in the National Park area with 311 visits having taken place by the end of 2022.

The visits and information submitted have revealed that the majority of monuments are affected by some sort of issue, including those likely to be exacerbated as a result of climate change. Specifically, almost three quarters of the monitored scheduled monuments are affected by scrub vegetation and almost a quarter by coastal erosion.

As a result of this monitoring scheme, the National Park Authority has and continues to use the data to prioritise and target resources in relation to land management activities relating to archaeological heritage. To date, the information has been used to target scrub clearance activities and also explore ways to mitigate and adapt to the impact of coastal erosion at affected sites.

Lake Vyrnwy Peatland Restoration by the RSPB

Lake Vyrnwy is the largest RSPB reserve in England and Wales, consisting of over 10,000 hectares of pasture, plantation, woodland and moors surrounding the Vyrnwy reservoir. There are extensive upland peat deposits in the west and north of the reserve. Drainage ditches cut into the peat, mostly excavated in the 20 th century, have eroded to form hags and gullies that decrease water retention and increase erosion. In future, higher temperatures, lower summer rainfall and more frequent storm events will contribute to erosion and cause peat shrinkage.

Peat erosion at the edge of channels at Lake Vyrnwy © RSPB

The uplands around Lake Vyrnwy contain a range of archaeological assets including Bronze Age barrows, a deserted Medieval settlement and agricultural landscape features. Although the area has been extensively surveyed (and the results recorded in the Historic Environment Record), many assets are poorly understood and there are many unrecorded or unknown features; these include visible earthworks, buried archaeological remains and palaeo-environmental information. These are all crucial to our understanding of the historic use of the uplands.

The RSPB has been carrying out peat restoration in selected upland locations at Lake Vyrnwy for several years, funded largely by Hafren Dyfrdwy and the NRW National Peatland Action Programme (NPAP), and carried out in accordance with the Peatland Code. It is a long-term project – the current plan will complete in 2055.

The RSPB has organised on-site training days at Lake Vyrnwy and remote training for those in the organisation involved in peat restoration. The training includes how to integrate heritage in restoration projects and how to recognise heritage features on the ground. This ensures that heritage is considered at an early stage and allows minor changes to be made by staff on site during works, thereby minimising delays.

Existing archaeological data has been supplemented by site visits by the RSPB archaeologist and any additional features will be added to the Historic Environment Record. Restoration proposals are discussed with the RSPB Archaeologist and plans can be adapted to avoid impact on heritage assets.

The gradual re-wetting of the peat is slowing and could potentially stop the degradation of known and unknown heritage assets in the upland areas. This project is an example of nature focussed climate adaption that has had significant benefits for heritage.

Pools created by bunds at Lake Vyrnwy. A previously unrecorded archaeological feature, a bank of unknown date is in the background. © RSPB