Spatiotemporal Patterns of Eastern Spruce Budworm in Maine

Overview

What's all the fuss about?

An image of the Eastern Spruce Budworm

The Eastern Spruce Budworm is a species of naturally occurring insect that thrives in spruce-fir dominant forest. Adult moths mate and lay eggs in clusters of 10-150 on the needles of host trees between July and August.

Larvae hibernate through the winter and feed on new foliage in the spring. Moths emerge from pupae beginning in July, when they will mate and lay eggs, starting their life cycle once again.

Why is this a problem for Maine?

An image of a northern Maine forest where the has begun to defoliate some spruce-fir tree tops.

Repeated life cycles of the spruce budworm feasting on trees stsands can lead to years of increased defoliation, leaving the host tree to die in about 4-5 years.

Large outbreaks of the budworm within the state can lead to large portions of the spruce-fir dominant forest becoming susceptible to defolation and die-off.

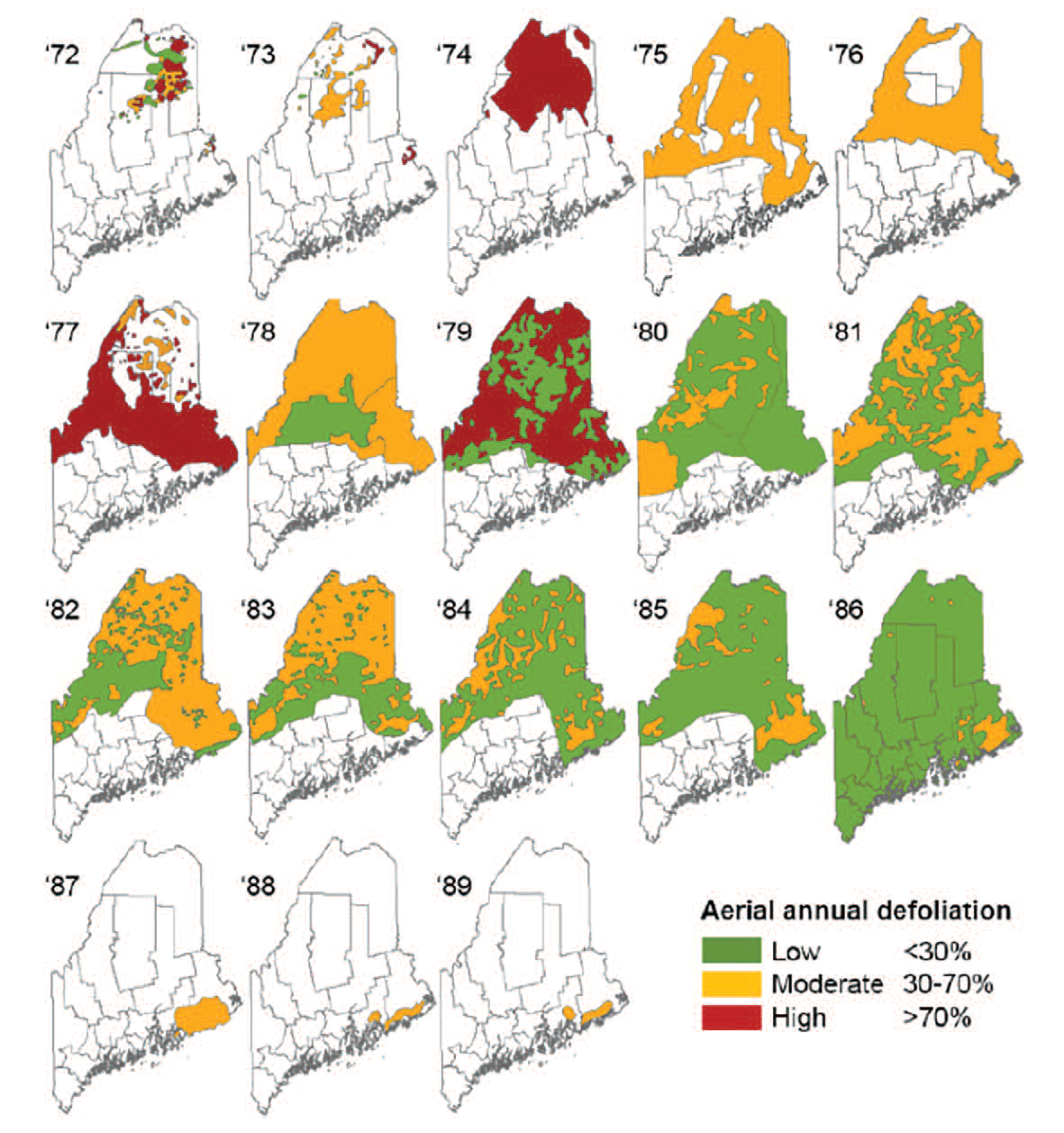

We know this because it has happened before. In modern times, Eastern Spruce Budworm outbreaks have occurred in the 1910’s, 1940’s, and the 1970’s, suggesting that an outbreak is due to happen any time now.

During the last outbreak in northern Maine, defoliation of balsam fir led to 84% to 97% mortality of affected trees.

Moth Trap Analysis

In order to see the spatial trend of moths in the forest, moth traps were placed around the state to collect population data.

Here, we can see the counties within the state.

This layer shows all 602 budworm trap sites that were placed within the forest.

Three traps were placed per site and were pulled after a period of time.

When pulled, the moths that were caught in the traps were counted and an average of all three traps was taken to display the data we see to the right.

Image of a spruce budworm moth trap in the Maine forest.

The counties layer and the budworm trap layer were dissolved together, with the join coint showing traps per county.

Higher counts are shown in purple, while smaller counts are shown in lighter shades.

The multivariate cluster tool was used to generate clusters based off of similar population trends from 2014-2023.

Clusters are not in sequential order, but rather formed with features expressing similar population trends over the 10 years studied.

Cluster 3 has the fewest features but the highest moth counts, so these areas should be monitored closely.

The multivariate cluster layer displayed as features per cluster to show the amount of features related to moth counts

The multivariate cluster layer displayed as a box plot

Isolating Clusters 3 and 4

Clusters 3 and 4 had anomalies that showed up mainly in Aroostook County, but also traveling southward into Penobscot county.

Legend describing the different landowner types

Thanks to the Maine Forest Products Council, they produced a map of the large land owners.

When compared to the cluster anomalies, we can see that most of Cluster 3 sits on family-owned land in Aroostook County. Perhaps a mix of being closest to the Canadian border, along with less incentive to enact mitigation practices has allowed for budworm populations to soar. These land owners should be made aware that budworm moths have been migrating south so they can prepare to protect their property.

The industrial land in northern Maine is also experiencing anomalies, yet there is a far greater incentive for industrial landowners to enact mitigation tactics to curb any negative economic impact to their timber.

Cluster 4 had less severe budworm increases overall, but still had significant outlying spikes in similar years. These clusters have moved down into Penobscot County, which should start preparing for a greater influx of spruce budworm.

Kernel density maps for every year from 2014 to 2023

The kernel density tool was run for every year from 2014 to 2023 to display the hot spots of budworm moths.

There was an increase in moths from 2014 to 2016, and then a decrease from 2017 until 2021.

There was a slight increase again from 2021 to 2022, and a drop off in 2023 where there is minimal activity. This could be partially because of the lack of data for the year 2023.

A kernel density map of the average moth hot spots from 2014-2023

Tree Host Species

Despite its name, the Eastern Spruce Budworm is most damaging to balsam fir trees. Spruce is affected to a lesser degree than fir, with more damage being caused to white spruce, and less on red and black spruce.

Despite its name, the Eastern Spruce Budworm is most damaging to balsam fir trees. Spruce is affected to a lesser degree than fir, with more damage being caused to white spruce, and less on red and black spruce.

The Individual Hosts

The North Maine Woods are dominated by spruce-fir forest.

The process of accurately identifying individual tree species and their biomass percentage can take a lot of time and computational power. Because of this, the data for tree-species ground coverage here in Map 3 confined to this (approx.) 9,000 sq. mile space, while the total land area of Maine is almost 31,000 sq. miles.

Regardless of its limitations, this data gives us insight on how Maine’s environment impacts the survival tactics of the SBW.

The following maps will illustrate how much more ground coverage Balsam Fir takes up– perhaps the “Spruce” Budworm actually prefers Balsam Fir in Maine simply because Balsam Fir is far more common!

White Spruce (Picea glauca)

White Spruce has a somewhat even spread, with slightly higher concentrations occurring in the northern part of the state.

Black Spruce (Picea mariana)

Black spruce tends to prefer cool upland soils, but is also found along streams and bordering swamps.

The highest concentration of black spruce occurs in the northwest part of the state right near Canada.

Red Spruce (Picea rubens)

The most abundant spruce variety in the state, it prefers well-drained, rocky upland soils.

The highest concentrations of this species can be found in the areas surrounding Baxter State Park, which is home to Mt. Katahdin, the highest peak in Maine.

Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea)

As the most abundant tree in Maine's forest, balsam fir dominates the landscape.

Trees are spread rather evenly in high percentages throughout, prefering areas of well-drained soil on hillsides, yet also prefering lower elevations with damp woods, such as in river and stream valleys.

SBW vs. Tree Species

Identifying Budworm Population Growth

Here, we can compare the host tree species composition to the Spruce budworm surge of 2022-23, where the four areas of increase are noted at the US and Canadian border in the northwesternmost part of the state.

The isolated SBW increase in dominant (>50% biomass) host trees composition map can help pinpoint vulnerable forest areas for SBW thriving environment.

There are four areas that needs immediate attention and can be a hot spot for early SBW outbreak.

Trap ID: MFS - 1515

2022: 46 2023: 329.7

Buffered zones of 100m, 500m, 2000m in MFS-1515 shows significant increases where spruce-fir dominant forest is also present. Especially in 2000m zone at the border with Canada, abundant spruce-fir biomass is largely accessible to grow a SBW population.

This region is also adjacent to the Canadian outbreak, providing easy access for large moth populations.

Trap ID: IRV - 1813

2022: 32.7 2023: 100

Similarly, the result in this location indicates a budworm growth despite being in the no data (black) pin. The close proximity and SBW trap locations to spruce-fir dominant forest shows the correlation the high increase of SBW.

Trap ID: IRV - 1511

2022: 5.3 2023: 86

IRV - 1511 shows SBW increase greater than 50 , even among less dominant host trees.

This could be due to there being 3 pheromone traps per moth site and obtaining the moth average; we do not have data on where they were actually placed, so they may have ended up in a singular red or orange pixel stand of dominant spruce-fir, despite the majority of pixels being non-dominant.

Identifying Declines in Budworm Population

The top 5 locations that report significant increase are spread out in Northern Maine. We have focused on places in the western portion, where host tree composition data was available.

Trap ID: SI - 1614

2022: 106.7 2023: 28

SI-1614 lacks data in many areas. These areas could represent water or areas of deciduous trees, both being unfavorable conditions for the budworm to thrive.

Trap ID: MFS - RUS

2022: 53 2023: 2

This location had an almost total annihilation of SBW, despite having spruce-fir dominant forest in its immediate 100m buffer.

The neighborhood forest stands are composed of less spruce-fir biomass, and possibly SBW do not have enough food to grow its population.

Trap ID: PC - 512

2022: 61.7 2023: 6

The consistent low host biomass in this trap location (PC-512) show decrease from 61.7 to 6 SBW on average in 2023. It confirms the thesis that SBW will not flourish in forests low in balsam fir and spruces species.

The spatial distribution of all decreases and the top 5 decreases were spread randomly through the north and central state of Maine.

While we identified the top 5 sites with decreases, let's compare the forest composition of some additional traps that had less significant decreases.

Trap ID: LV - 1214

2022: 66 2023: 39.3

LV-1214 had a year over year decrease, but less significant. This could indicate an established population that can endure several years of growth and contraction. There are enough host trees in the 100m and 500m buffer for the moths to feed on.

Areas such as this should have more monitoring stations placed to track this potential established moth colony.

Trap ID: PC - SMITH

2022: 53.3 2023: 10

PC - SMITH trap is the furthest place south for SBW moth decrease location. The trap is among host trees, but the decrease may be related to warmer climate or spatial position in relativity to other traps. The moth might be more restricted to grow its population because of isolated host tree stands.

SBW vs. Tree Maturity

Forest Maturity

Maine's forest is a decent mix of mature and non-mature trees, with a slightly higher number of mature trees.

How the map was produced

The data to access the tree height used 2021 photogrammetric point cloud data along with high resolution (1m) Digital Elevation Models (DEM). The noisiness of photogrammetric point cloud was calculated into 10m resolution to estimate tree canopy height by allowing 95% of the tree height within each 10mX10m cell to be below 26m, and 5% above 26m. The data include most of the state of Maine and show most reasonable estimation of distribution pattern of coniferous and deciduous forest combined.

Trees are classified based on tree height:

<12m = Non-mature >12m = Mature

Setting a height threshold of 12m shows that the distribution of all trees skews slightly more mature.

Anomalous Increases

These locations are defined by having a 2023 moth count greater than 50, and also having had a total moth count increase greater than 50 from the previous year.

Four locations of further interest were identified, which all occurred in the northwestern-most region of the state.

Trap ID: MFS - B20

2022: 18 2023: 167.7

The trap shows increase in mature forest location where canopy is the thickest.

Trap ID: IRV - 1813

2022: 32.7 2023: 100

Reason for irregularity in this location might be data discrepancies of 2021 and budworm averages of 2022-23, where black areas might be related to timber harvesting.

Trap ID: MFS - 1515

2022: 46 2023: 329.7

Huge increase of SBW in this site where mature forest is present, and nearby forest is also mature, prone to SBW defoliation. Might be the area of focus for targeted mitigation practices.

Trap ID: IRV-1511

2022: 5.3 2023: 86

High content of mature forest in this site and its proximity may provide enough food for budworm to quickly multiply.

Anomalous Decreases

These locations are defined by having a 2023 moth count fewer than 50, and also having had a total moth count decrease greater than 50 from the previous year.

Ten locations were identified, with the four largest anomalies explored below in greater detail.

Trap ID: MFS - MDA

2022: 221.3 2023: 5.3

Significant decrease of budworm may be due to the fact that there is non-mature forest to live on.

Trap ID: SI - 1614

2022: 106.7 2023: 28

The drop budworm average in 2023 in mature forest (SBW favorite forest type) might be because the traps are placed among mature deciduous or mixed forest trees, which are non-host species.

Trap ID: SI - 126

2022: 81.7 2023: 1.7

Despite being in a region of mature-dominant forest, we saw significant decreases at SI - 126. These decreases could be due to other factors such as elevation or climate.

Trap ID: PC - 512

2022: 61.7 2023: 6

Similar unexplained decreases in areas of mature-dominant forest are seen at PC - 512.

The Python script code (using PyCharm) has been created to automate data normalization of the host tree species against the softwood tree species of Maine forest.

Special thanks to Dr. Kasey Legaard for his input in the coding. The normalized data could be analyzed efficiently and with high accuracy.

SBW vs. Climate

For a relatively small state, Maine has 3 distinct climate types covering its scope. All of them can be broadly considered humid continental.

Southern and coastal Maine gets more mild summers and winters from the influence of the Atlantic...

In Map 5 we specifically only isolated increases and displayed every year we have SBW moth counts for. It’s clear the SBW has a strong preference for cooler temperatures in northern Maine around Aroostook County. To quote a paper from Elsevier, “Defoliation intensity can be lower with warmer minimum spring temperatures when the temperature increase is insufficient for the larvae to end their diapauses [hibernation/arrested development].” As the region continues to see temperatures rises, might we see a continued northern-migration of the SBW, or will they adapt with the changing climate?

...whereas the more northern continental climate of Maine has mild summers but colder and snowier winters. The northward colder regions of Maine are where we see the SBW reside.

For this series of maps, we isolated for increase/decrease in SBW from one year to the next using a tipping point of 50 moths counted per trap. In 2016 there were no increases from under 50 in 2015 to over 50 in 2016.

But in 2017 we see several locations along the Maine/Quebec border with rises above our 50-count threshold.

It’s clear the SBW has a strong preference for cooler temperatures around Aroostook County.

To quote a paper from Elsevier, “Defoliation intensity can be lower with warmer minimum spring temperatures when the temperature increase is insufficient for the larvae to end their diapauses [hibernation/arrested development].”

As the region continues to see warmer springtime temperatures, might we see a continued northern migration of the SBW, or will they adapt with the changing climate?

Researchers collecting SBW samples from 1962 outbreak

As for population fluctuations attributable to maximum temperature, these results are inconclusive. It seems regardless of springtime temperature variations over 2016-2023, the increase/decrease is more oriented with northward continental position than it is with warmer/cooler areas of the north.

For example, on this map we have narrowed down SBW traps to only locations that have seen consistent growth in population over 5 years (2016, 17, 18, 19, 20). None of the three locations are in the westward coldest regions of Maine, but they are in the northern continental climate zone.

SBW vs. Landscape

To get a fuller picture of the preferred SBW habitat, this next series of maps uses a DEM (Digital Elevation Model) that shows how far above or below average a given point is relative to its surroundings. The radius around a point to get this average is between 1,500 and 5,000 meters.

Here we are looking at all 602 moth trap sites to get an idea of the wide net that has been cast.

These pinpoints are areas where there's been a consistent growth in population over 3 years (18, 19, 20).

And notice the preference for much lower elevations.

Overlaying the DEM is a tree species DTM (Digital Terrain Model) that is isolating only for Balsam Fir, the tree of choice in Maine for the SBW. The legend shows percent of on-the-ground biomass coverage, and anything with less than 10% is filtered out with "no color."

A closer look shows that Balsam Fir prefers the lower elevations too.

Unfortunately, our DTM for the Balsam Fir is limited in its scope to just a northwestern block of Maine. But if we can assume the eastern half of Maine has about the same level of Balsam Fir coverage, then also grant that it continues to thrive best in lower elevations, this is a strong indicator for why most of our SBW increases are seen in the northeast in lower elevation terrain.

Only 3 locations out of a possible 602 saw a 5-year increase!

Of these 3 spots, only one was 1.3 meters above average for the region, while the other two locations are significantly below average: -2.3 and -6.4 meters.

Westmanland, county of Aroostook

Pheromone moth trap average increases starting in 2016:

2016 – 3 SBW 2017 – 29.5 SBW 2018 – 44 SBW 2019 – 82.7 SBW 2020 – 186.3 SBW

T10 R6 WELS, an unincorporated township in county of Aroostook

Pheromone moth trap average increases:

2016 – 9.7 SBW 2017 – 13 SBW 2018 – 50.7 SBW 2019 – 53.3 SBW 2020 – 97.3 SBW

Merrill, in Aroostook County

Pheromone moth trap average increases: 2016 – 7.3 SBW 2017 – 11.7 SBW 2018 – 12 SBW 2019 – 37.3 SBW 2020 – 55 SBW

It remains to be seen how severe the upcoming outbreak will be, but the shifting climate conditions in Maine do set up unprecedented conditions for all wildlife. We may find that the SBW is no longer well-suited for the warming environment in Maine– or, we may see the SBW adapt to the changing conditions. During the scope of this project we have narrowed down that SBW is likely to be found in lower elevations in cooler environments in the north/northeast, and if Balsam Fir can thrive, then so can the budworm.

THANK YOU, ERIN & KASEY!

Thank you for all the advice and guidance you provided throughout this internship. Hopefully this data analysis can be useful to you as you continue to study this problem! Your knowledge and expertise were the foundation of this work, and we would not have been able to do any of this without your help and previous research.

Otherwise, we'd be lost on a mountain in Maine ;)

References

Cooperative Forestry Research Unit. (2016). Coming Spruce Budworm Outbreak. University of Maine.

Institute, S. N. (2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, April). ClimatologyLab.org. Retrieved from https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html

Jerald E. Dewey, U. F. (2001, March 30th). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Choristoneura_fumiferana_larva.jpg

Subedi, A., Marchand, P., Bergeron, Y., Morin, H., & Montoro Girona, M. (2023). Climatic conditions modulate the effect of spruce budworm outbreaks on . Elsevier, 13.

USDA Forest Service, R. 6. (1062, June 28th). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1962._Collecting_western_spruce_budworm_larvae._Goldendale,_Washington._(36069366645).jpg

Balsam Fir (Abies Balsamea), White Spruce (Picea Glauca), and Red Spruce (Picea Rubens) | Maine Natural History Observatory. www.mainenaturalhistory.org/node/585.

Maine Office of GIS. www.maine.gov/megis.

“The University of Maine.” The University of Maine, umaine.edu.

Coming Spruce Budworm Outbreak:, www.sprucebudwormmaine.org/docs/SBW_full_report_web.pdf.